In conversation with Hanna Hölling, Emilie Magnin and Valerian Maly, Eléonore Hellio and Michel Ekeba of the collective Kongo Astronauts discuss the origins, ongoing evolution and potential futures of their multifaceted artistic practice. They explain the circumstances that first brought Hellio, who was born in Paris, to Kinshasa, and relate Ekeba’s first experiments with wearing an astronaut costume that he made of discarded electronics purchased at a market. Conservation is figured partly in terms of the astronaut costumes, which are constantly changing through cycles of use and repair, but which also have the potential to be purchased as artworks and conserved as static museum objects. Hellio and Ekeba also discuss the films and photographs they produce, which both propagate and disseminate the live performances that take place in Kinshasa. Finally, conservation is also understood in the collaborative, social practices of Kongo Astronauts, which are taken up, reconfigured and renewed by the various artists who pass through the collective. Ekeba and Hellio also relate the performative and ritual aspects of their work to traditional Congolese practices suppressed by colonial authorities. Introduction by Jacob Badcock.

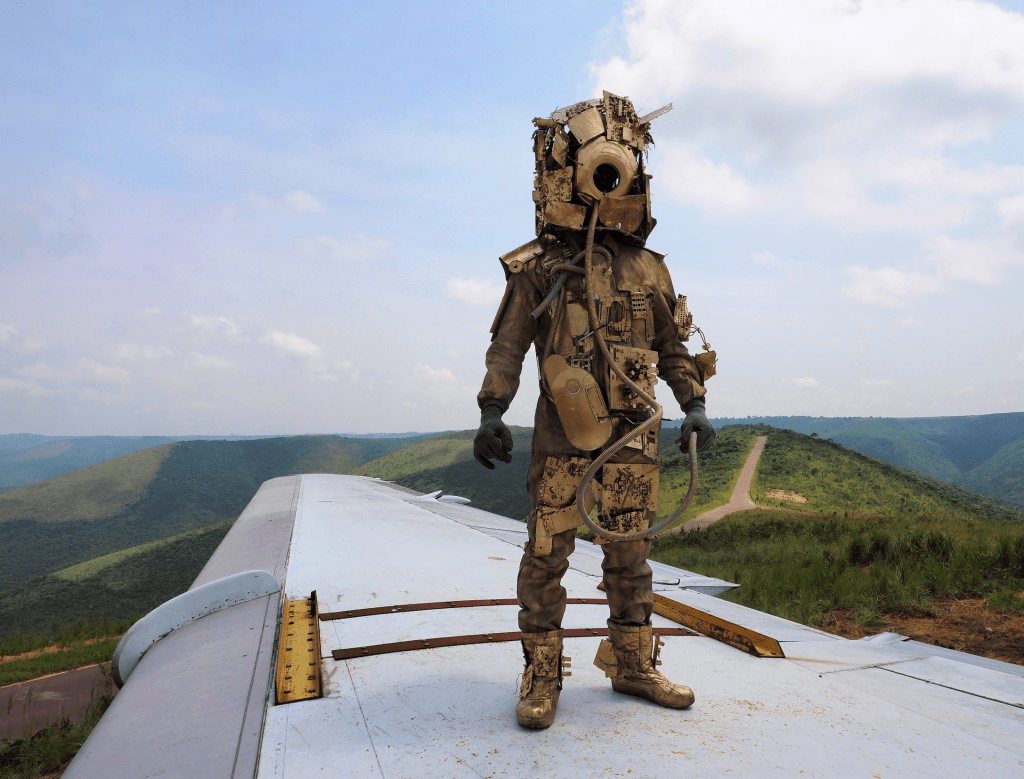

Writing in “Further Considerations on Afrofuturism” Kodwo Eshun asks us to “imagine a team of African archaeologists from the future […] excavating a site, a museum from their past: a museum whose ruined documents and leaking disks are identifiable as belonging to our present.”1 Kongo Astronauts, an artist collective founded in 2013 by the Kinshasa-based artists Eléonore Hellio and Michel Ekeba, are the image of the Afrofuturist archeologist par excellence. Kongo Astronauts are perhaps best known for their images of travel—the lone astronaut, dressed in a metallic suit plastered with digital detritus made from minerals mined in Democratic Republic of the Congo and subsequently returned to it in the form of technological waste. The costume painfully explicates the crises of extractive capitalism and environmental racism. Kongo Astronauts’ multi-media practice includes photography, film, sculpture and performance, and engages with Kinshasa’s alternative cultural network. In their creative practice, both the urban postcolonial pandemonium and the forces that have shaped the artists’ immediate environment are intertwined with a critical lens, through which they assess human condition in contemporary Congo.

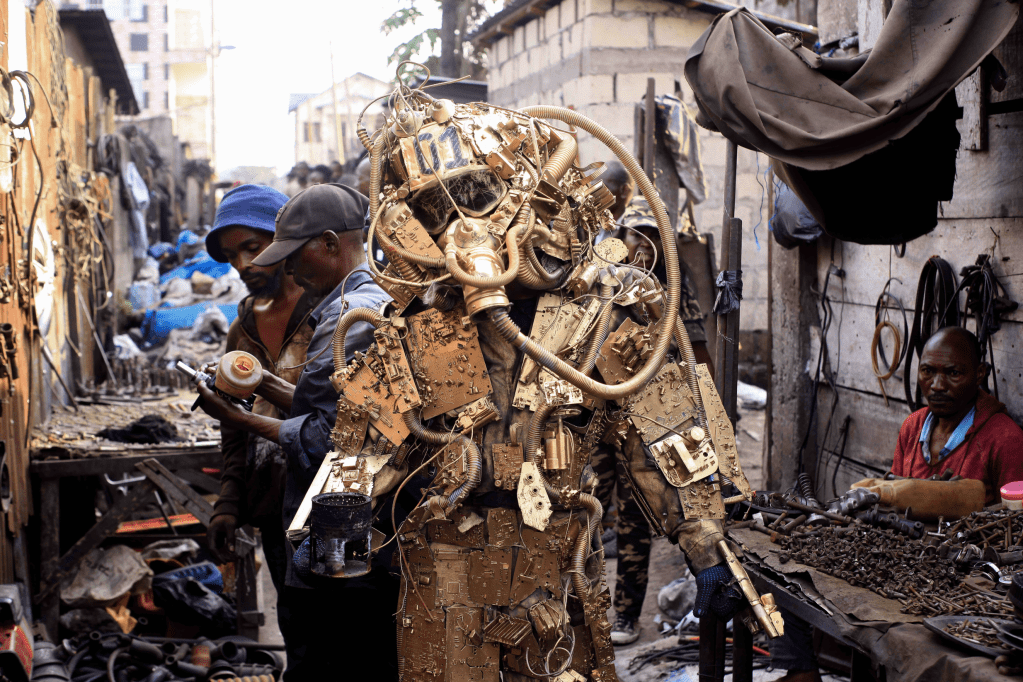

Figure 10.1. Kongo Astronauts, Untitled [-5], 2021, Series: SCrashed_Capital.exe. Fine

art Baryta paper. Courtesy: Kongo Astronauts and Axis Gallery. The image as published on page 210.

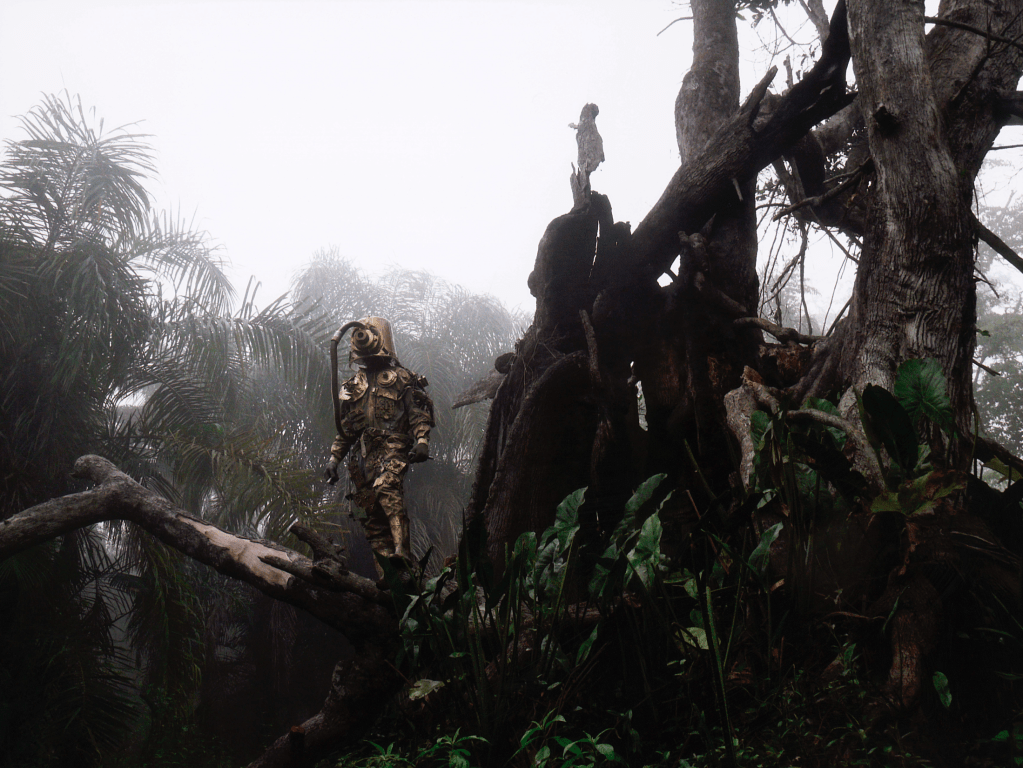

Helio: In our work together as Kongo Astronauts, we question the many impacts of mining the earth and beyond, on these quests for mining infinity endlessly. Thinkers, artists and innovators from Africa have to propose their vision of the future and not only be consumers or, worse, casualties, as was and is so often the case. The performance of the astronaut is also a way to adapt to a globalized, fast-changing world, and to find an equilibrium between resistance and assimilation. Lastly, the astronaut’s performances address the Earth’s condition and ecology. They demonstrate the obscene gaps between the North and the South. The figure of the astronaut can be seen as a contemporary mask. In Congolese traditions, the mask is conceived as a school for sharing knowledge and experience. The mask thus questions the current political, social, and economic status quo in Congolese society, and it questions Congolese identity. However, it is important to realize that the term “identity” is not used in day-to-day discussions— the self-reflection that this notion requires is mainly centered around the interaction with the Western world.

Figure 10.2 Kongo Astronauts, The jungle is my church 1, 2015. Series: Lusanga “ex:Leverville.”

Fine art Baryta paper. Courtesy: Kongo Astronauts and Axis Gallery. The image as published on page 211.

Ekba: The electronic parts, the circuit boards of the Kongo Astronaut’s suit are sold in bulk at the market. I buy them there, I don’t pick them up because you can’t find them. There is a market of resellers of electronic parts where you can buy diodes and all the other small parts used to repair stuff, all in good condition. Kongo Astronauts’ work addresses the exploitation and conservation of minerals and ores in Congo. By creating the suits in gold and silver, we make a link to these natural resources and all the wealth that exists in the country. There is an unlimited connection between matter and creation. An old phone comes back to the place from which the resources originated. To create a costume is to participate in the never-ending process of extraction, exploitation, fabrication, destruction, reconstruction, transformation…

Helio: This practice of using recycled materials is also characteristic of DRC. As an example, having grown up in Mbandaka, in the equatorial region of Congo, Bebson is very knowledgeable about traditional musical instruments used in that region. When he moved to the capital, he didn’t have access to these instruments, but he had their sounds and shapes in his memory. He didn’t have the money to buy modern instruments imported from Europe, America or Asia. So street children supplied him with found materials gathered in the streets—broken objects like kitchen utensils, electronic toys, sound systems, car parts, etcetera. Bebson mastered the DIY philosophy and recreated all the sounds he grew up with, including the wind blowing between the trees in the forest or the hatching of a thousand caterpillars… mixing it with new sounds made of industrial waste. But Bebson doesn’t keep things, he feels he needs to continuously rebuild the world and reconfigure his dreams. If something breaks, he makes something else. He doesn’t emphasize preservation. His idea of preservation is embodied in the school that he created in the neighborhood: “If you don’t have money, create an instrument with whatever you have at hand.” It’s an ongoing bricolage. And Bebson’s creations are difficult to preserve since they are made with whatever is at hand at the given time and last a limited time. I feel a very strong affinity with Bebson, but maybe for you it’s different, Michel?

Ekba: Well, Bebson inspired many artists, and I was inspired by Bebson in the way he makes things out of anything. But I wanted to keep, not destroy what I had built. Like a musician, who is inspired, and who takes a melody and changes it. Bebson is a part of us, a spirit to which we dance. For me, Kongo Astronauts has allowed me to reconstruct myself. In it, I preserve the gems of my land. The costume allows me to preserve the knowledge and to preserve who I am. It’s a form of identity.

Figure 10.3 Kongo Astronauts, Aisle of Dreams, 2019. Series: After Schengen. Fine art

Baryta paper. Courtesy: Kongo Astronauts and Axis Gallery. The image as published on page 212.

This is an excerpt from chapter 10 of the recently published volume Performance: The Ethics and the Politics of Conservation and Care, Vol. 1, edited by Hanna B. Hölling, Jules Pelta Feldman and Emilie Magnin. London and New York: Routledge, 2023. To continue reading this chapter, follow this link. To access Vol. 1 Open Access, click here.

DOI:10.4324/9781003309987-13