Check out the latest article, “Reperformance, Reenactment, Simulation: Notes on The Conservation Of Performance Art,” penned by our colleague Jules Pelta Feldman, a valuable contribution to the scientific output of SNSF Performance: Conservation, Materiality, Knowledge.

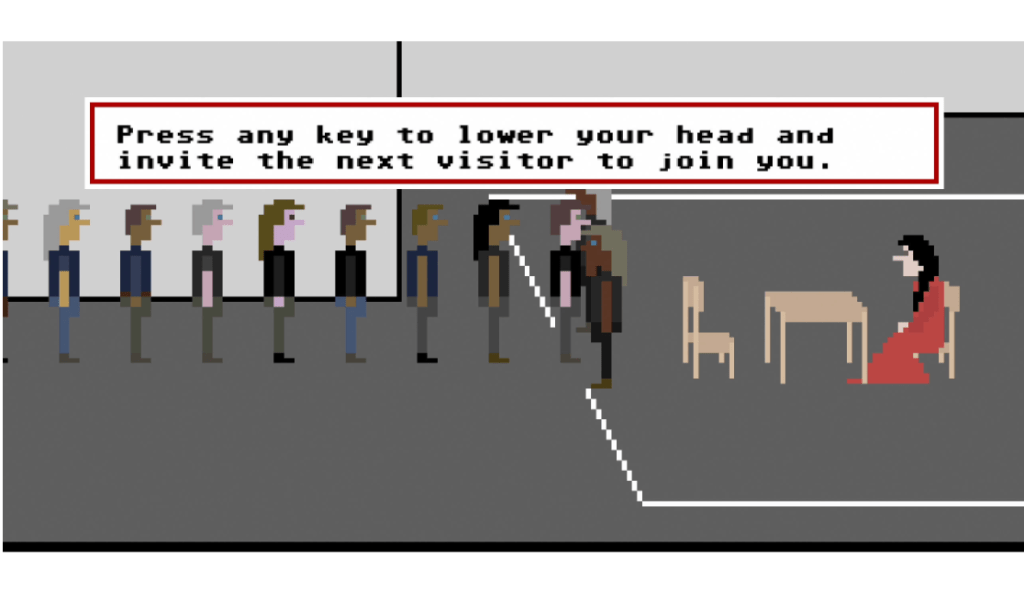

In this essay, they explore a novel perspective on preserving performance art by employing simulation. The article investigates how simulation effectively captures the historical context and experience of Marina Abramović’s works. From reenactments to video games, these simulations redefine our understanding of conserving performance art.

Below is a snippet from the essay, with the complete open-access version available through 21: INQUIRIES INTO ART, HISTORY, AND THE VISUAL: https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/xxi/article/view/100738/97004

Art conservation has traditionally been considered to encompass two types of activities: restoration and preservation. Restorative measures – known as “interventions” – repair damage or undesirable changes. In the case of a traditional art object, this might mean replacing paint that has detached from its support, reassembling fragments of a shattered vase, or cleaning rust from metal. Preservative measures are intended to prevent such damage – usually, to minimize changes.1 Preservation avoids intervening in the object itself, and includes measures like climate control, protection from ultraviolet rays, proper storage and handling, and the velvet ropes that keep museum visitors from getting too close. It also includes documentation, which, though long essential to conservation, has become an increasingly important part of conservators’ work in recent decades.While seemingly conventional artworks frequently present conservation quandaries, performance art’s challenge to the discipline approaches the existential. In the case of performance, which has often been considered too different from paintings, sculptures, or even electronic media to be conserved, conservation strategies may be similar or even identical to curatorial ones: documents like photographs and videos are the most common way of “exhibiting” historical performance. And in the absence of an authoritative object, the division of conservation activities into restoration and preservation seems difficult to apply. A performance’s traces – its various documents and relics – can be conserved, but how can one do more than document a performance? And beyond maintaining extant materials, what might a conservation intervention – an attempt to restore something already lost or damaged – look like? One answer to this question might be found in the practice known as “reperformance”, through which artists revisit works of historical performance by presenting them live. Yet reperformance has been widely criticized by scholars of performance. For while it allows for live transmission of certain aspects of a given work, such as interaction between performer and audience, reperformance neglects other qualities that scholars tend to consider vital to its meaning, even if these characteristics are not part of the work itself, such as historical context or geographical site. In short, reperformance as a conservation strategy focuses on aesthetic fidelity at the expense of historical fidelity. In what follows, I propose to separate these two important but conflicting perspectives, imagining the possibilities of a historically sited form of preservation that is, unlike documentation, nonetheless grounded in the viewer’s own experience. Using the work of Marina Abramović, reperformance’s most influential and controversial practitioner, I present simulation – the real-time imitation or modeling of a process, system, or event – as a viable approach to the conservation of performance that circumvents the key criticisms leveled at reperformance. Simulation can be described as “mimetic documentation” – a reconstruction of a performance that may claim to conserve it by recouping aspects that would otherwise be, or already have been, lost. To make this argument, I will first discuss the limits and critique of reperformance, and then turn to simulation as an alternative approach, instances of which may be found in historical reenactment, cinema and television, and video games. Each suggests other mediations of performance that hold the potential to preserve, present, and convey aspects of performance art – even embodied experience – that are otherwise unavailable in traditional forms of documentation or existing conservation approaches.