In chapter 13 of our recently published volume Performance: The Ethics and the Politics of Conservation and Care, artist and archivist Cori Olinghouse and art historian Megan Metcalf employ four illustrative examples to explore how an embodied approach to archives and acquisitions transforms traditional conservation paradigms. They critically examine the evolving vocabulary for the continuation of performance over the long term—which spans art and dance history, museum and archival studies, and conservation theory and practice—while supplying lessons learned through decades of practice and research. In the course of their conversation, the two speakers identify a skill set as well as emerging principles for archiving forms with performance elements, calling for a generative, artist- and community-based approach to conservation. Beginning from the premise that dance and other performance forms have inherent strategies for continuation that mitigate against their assumed ephemerality, this dialogue maps rich ground for conservation of all kinds.

Project #1

Trisha Brown and Sylvia Palacios Whitman, Pamplona Stones (1974)

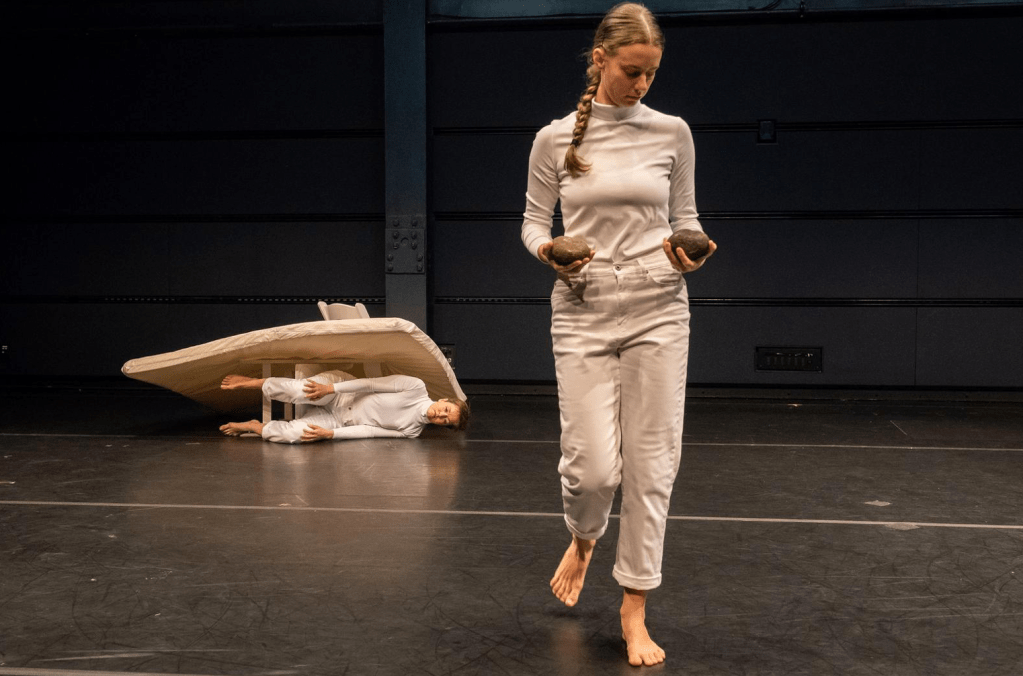

Pamplona Stones was created and performed in 1974 by Trisha Brown and Sylvia Palacios Whitman. Their humorous eighteen-minute duet consists of serial actions carried out in a nonchalant, deadpan style with a variety of props, accompanied by flat, monotone speech. The objects include two palm-sized rocks, a provisional tent-like structure with a sheet and two poles, and a small mattress, which they arrange and rearrange to make visual and verbal puns. Brown described the work as “a careful distribution of words, objects, and gestures in a large square room with an interplay of ambiguity in language and reference—a multiple theme and variations.”[1]

Megan Metcalf: In our respective art history and archiving practices, Cori and I have noticed that the phrase “body to body transmission” is increasingly invoked by museums and conservators and curators, but the how of that is not often addressed.[2] And that’s what we feel intimately involved in. Cori, you’ve written, “It’s essential to be able to qualitatively understand how transmission is taking place, which means attuning to the memory structures that underlie particular forms.”[3] I feel this is at the heart of our dialogue today and that “attuning” is something I find so compelling about your work, Cori.[4] I take it to mean a careful process of observing the sensory details of a work and then finding a way to respond in a receptive feedback loop, which runs through all of your projects.

For example, Pamplona Stones was performed just a handful of times in the 1970s. Cori collaborated with the Trisha Brown Dance Company in 2018 to revive/reconstruct this piece (Figure 13.1). This work had fallen out of the repertory (or really had never been a part of the repertory of the company). In a dance company, the “repertory” is the collection of dances that a dance company stewards or holds. “Active repertory” is comprised of the dances the performers currently know and are performing, with other dances from the repertory restaged or “revived” by way of embodied knowledge transfer. This transfer is usually directed by someone who has performed the work in the past: they teach the choreography (sequences of steps, movement patterns, and body shapes) to a new generation of dancers, typically drawing on their first-person experience as well as recordings of the work. “Reconstruction” of a dance is generally reserved for circumstances when only fragments of the dance remain, or if a long time has passed since the work has been revived.[5] It was clear early on in Pamplona Stones that the usual revival or reconstruction process wasn’t going to work for this piece.

Cori Olinghouse: For Pamplona Stones, my intention as a restager was to let humor be the guide. For the jokes to register to an audience, the performers would need to learn to follow their own amusements rather than performing the work solely as abstract choreography. Part of my approach was to help the dancers attune to the rhythms and timings between the words, actions, and gestures. I had archival material to work from, but it was important for me to spend immersive time with Sylvia Palacios Whitman, whose own relationship to humor in her performance work was so instrumental to the making of the piece. Sylvia performed early on with Trisha Brown, and in 1974, shared a concert of her own works in Trisha’s fifth‐floor loft at 541 Broadway. Sylvia was a pivotal force during the performance art of the 1960s and 70s, and she remains active today.[6] Her works are populated by surreal stage props (both found and made), which include: gigantic green hands in Passing Through (1977), a smoking tea cup and large animal tail in Cup and Tail (1978), life-size drawings, and performative constructions such as a human slingshot entitled Slingshot (1975), and a water fountain made of bare legs splashing in water.[7] The influence of this visual vocabulary and comedic sensibility on Pamplona Stones is clearly evident.

Sylvia and I spent a week together in a residency that I structured as a physicalized oral history process. At that point, Trisha had already passed away and, while I was unable to work with her on Pamplona Stones, my experience working with her in the company and with the archive had given me intimate time with her practice and methods. Pamplona Stones—a work that took them only two days to create—took the performers and I over a month to reconstruct.

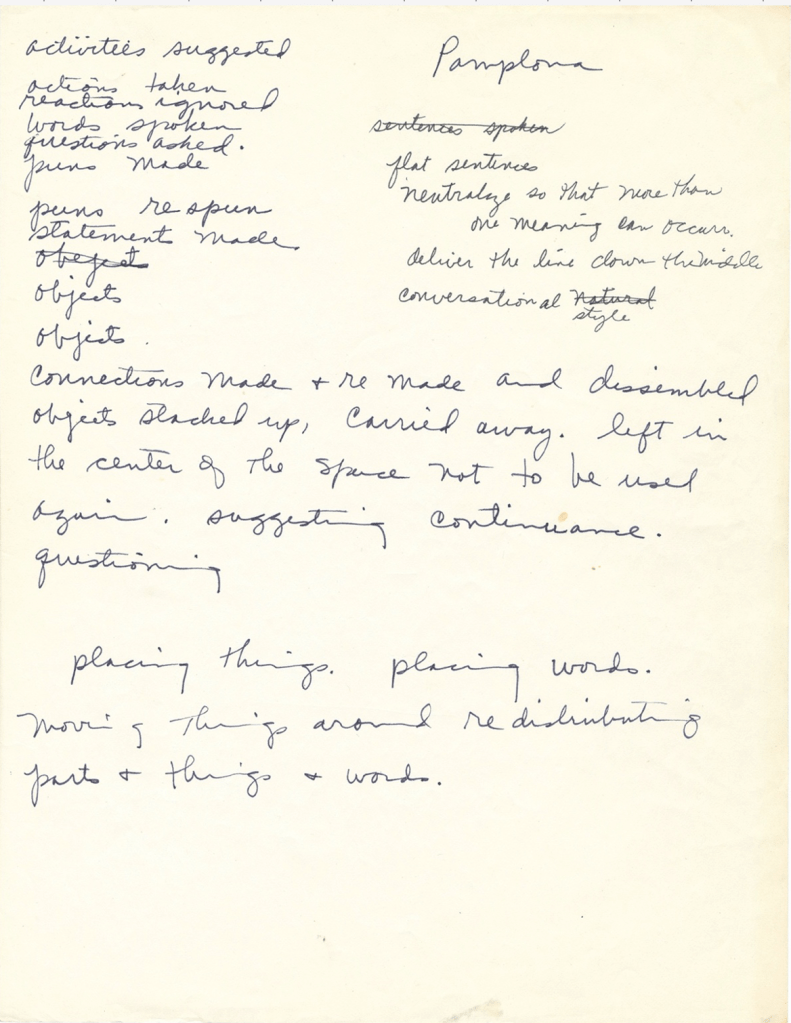

I used Trisha’s words as a blueprint or DNA for the work. In her original choreographic notes, she uses phrases like “actions taken, reaction ignored,” “puns made, puns respun,” “placing things, placing words,” “moving around, redistributing parts and things and words.” The clues provided in these words and the intimate time spent with Sylvia were instrumental to this process. As a secondary step, I used the words derived from Trisha’s choreographic notes as an improvisational score to recover the associative logic and the humorous impulses in the work (Figure 13.2).

Megan Metcalf: The duet is a very stripped down, simple interaction between these two performers. Cori, you have said it involves a negotiation of objects, words, the space, and each other. There’s not dancing in the sense of elaborate choreography. Your project was to mine the humor of it, not to reproduce the shapes that they were making. Is that a fair summary?

Cori Olinghouse: Yes, that was the challenge of it. In the end, I had to adhere to the choreography, which included the shapes, gestures, and words. I knew that the only way the performances would be animated was if the syntax of the joke structure was alive in ways that the performers could embody. So much of the spirit of this work emerges from Trisha’s and Sylvia’s personal relationship: they raised their kids together, they were friends in and out of the studio, and they’re both incredibly witty, hilarious people. It reminds me of Lucille Ball and Ethel Mertz from the 1950s American television sitcom “I Love Lucy,” the easy banter between friends. Their friendship is impossible to reproduce, and I wasn’t interested in asking the performers to mimic or imitate Sylvia and Trisha’s affects. Each performer brings their own personality.

I used improvisation to unearth the logic of the work, and to help make this more internal to the performers’ own sensibilities. In my practice in general, the possibilities of language have become essential to the way that I reconstruct performance works. For Pamplona Stones, I used a writing practice called “Rinse and Repeat,” that was inspired by Trisha’s own poetic use of language in her notebooks, which I transmitted to the performers as a way to elicit a thicker description and to attune to the humor. First, a segment of video is observed, then one performer moves continuously for 1-3 minutes. The other performer observes, using free association to describe what they are seeing in writing. At the end of the time period, the observer chooses a few resonant images from their writing as a score for movement. Then, the participants switch roles and the process is repeated.[8]

Some of the phrases the performers and I generated included: “deadpan, but without zombie,” “deadpan TV ritual,” “doing one action at a time,” “weird amounts of dead time,” “delayed reactions,” “all very anti-climactic.” I did this so the performers could internalize certain grammars about the work, while honoring their own agency, perspective, and improvisational impulses. Using this process, we made daily improvised versions of Pamplona Stones for one another.

I also carried out trial-and-error experiments with video documentation, using a 1974 video reference from the Walker Art Center. I experimented with replicating the forms in the video as choreographic grammar. I found that in trying to reproduce the choreographic gestures, there was a flattening or deadening of the work. Because Trisha and Sylvia are so stripped down, and so elegantly deadpan, it’s easy to miss the brightness and pathos operating at the same time. I began to jokingly refer to this process as “dance forensics,” which involves the myopic study and mimicry of the details from a recording.

This is an excerpt from chapter 13 of the recently published volume Performance: The Ethics and the Politics of Conservation and Care, Vol. 1, edited by Hanna B. Hölling, Jules Pelta Feldman and Emilie Magnin. London and New York: Routledge, 2023. To continue reading this chapter, follow this link. To access Vol. 1 Open Access, click here.

[1] Quoted in Trisha Brown—Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001 edited by Roland Aeschlimann, Hendel Teicher, and Maurice Berger (Andover, Mass: Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, 2002), 316.

[2] Theater and performance scholar Rebecca Schneider has theorized “body-to-body transmission” in relation to the ways performance resists disappearance, attributing the term to archivists Mary Edsall and Catherine Johnson. It is foregrounded throughout Schneider’s important book Performing Remains, which describes how movement and affect pass from one body to another through discipline, skill, and in-person contact, keeping embodied works alive across generations Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London and New York: Routledge, 2011). The term has been adopted since by curators such as Stuart Comer and historians such as Susan Rosenberg, who have used it to encompass a broad range of operations in dance and performance. See Nancy Lim, “MoMA Collects: Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions,” http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2016/01/27/moma-collects-simone-fortis-dance-constructions and Susan Rosenberg, Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2016).

[3] From Cori Olinghouse, “A Letter to the Future: Autumn Knight’s WALL (2016/2019) and the Studio Museum in Harlem,” in Performing Memory: Corporeality, Visuality, and Mobility after 1968, edited by Luisa Passerini and Dieter Reinisch (London: Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming).

[4] Olinghouse draws this term in part from affect theorist Kathleen Stewart’s concept of “atmospheric attunements,” which account for the ways lived sensory experiences have “rhythms, valences, moods, sensations, tempos, and lifespans.” Stewart writes, “How do people dwelling in them become attuned to the sense of something coming into existence?” See “Atmospheric Attunements,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29, no. 3 (2011): 445-453.

[5] In most dance scholarship, using “reconstruction” or “reenactment” to describe the restaging of a dance emphasizes the passage of time and the dance’s evolution in the process. See, for example, Mark Franko, “Repeatability, Reconstruction, and Beyond,” Theatre Journal 41, no. 1 (March 1989): 56-74. Also see Kim Jones’s account in “American Modernism: Reimagining Martha Graham’s Lost Imperial Gesture (1935),” Dance Research Journal 47 no. 3 (December 2015), 51-69, for another perspective on approaching the reconstruction process.

[6] The authors hold deep respect for the female-identified artists discussed in the following examples, i.e: Trisha Brown, Sylvia Palacios Whitman, Simone Forti, and Autumn Knight. We use their first names in our dialogue as an indicator of the intimacy that we have had working with them personally and to register the intimacy that performing this kind of embodied history and archiving requires.

[7] See Jay Sanders and J. Hoberman, Rituals of Rented Island: Object Theater, Loft Performance, and the New Psychodrama: Manhattan, 1970-1980 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013).

[8] “Rinse and Repeat” was developed around 2012 by Olinghouse’s collaborator and former Trisha Brown dancer Neal Beasley and was inspired by Trisha Brown’s work Rinse Variations in which she transcribed the choreography of Locus (1975) in writing and gave it to a group of artists to generate their own movement phrase. “Rinse” refers to the way that this “waters down” the Locus phrase, removing it further from the original version. The creation and identification of these strategies took place within the framework of “Transmissions,” a guide for an interdisciplinary arts curriculum that Olinghouse organized for the Trisha Brown Dance Company in 2017.