Don’t miss out on this impressive read: In Chapter 12 of our recently published volume Performance: The Ethics and the Politics of Conservation and Care, Karolina Wilczyńska dissects Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s Maintenance Art, contextualizing it within the notion of conservation. Titled, “Conserving a Performance about Conservation: Care and Preservation in Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s Maintenance Art,” her chapter revels that the very performance of conservation raises questions about how the same set of gestures could be oppressive, caring and emancipating at the same time. It further asks under what circumstances actions of preservation can be realized or reimagined. Examining Laderman Ukeles’s performance Transfer: The Maintenance of the Art Object (1973), Wilczynska demonstrates how the process of preservation is entangled in different political and institutional contexts, and what it means to conserve a performance about conservation.

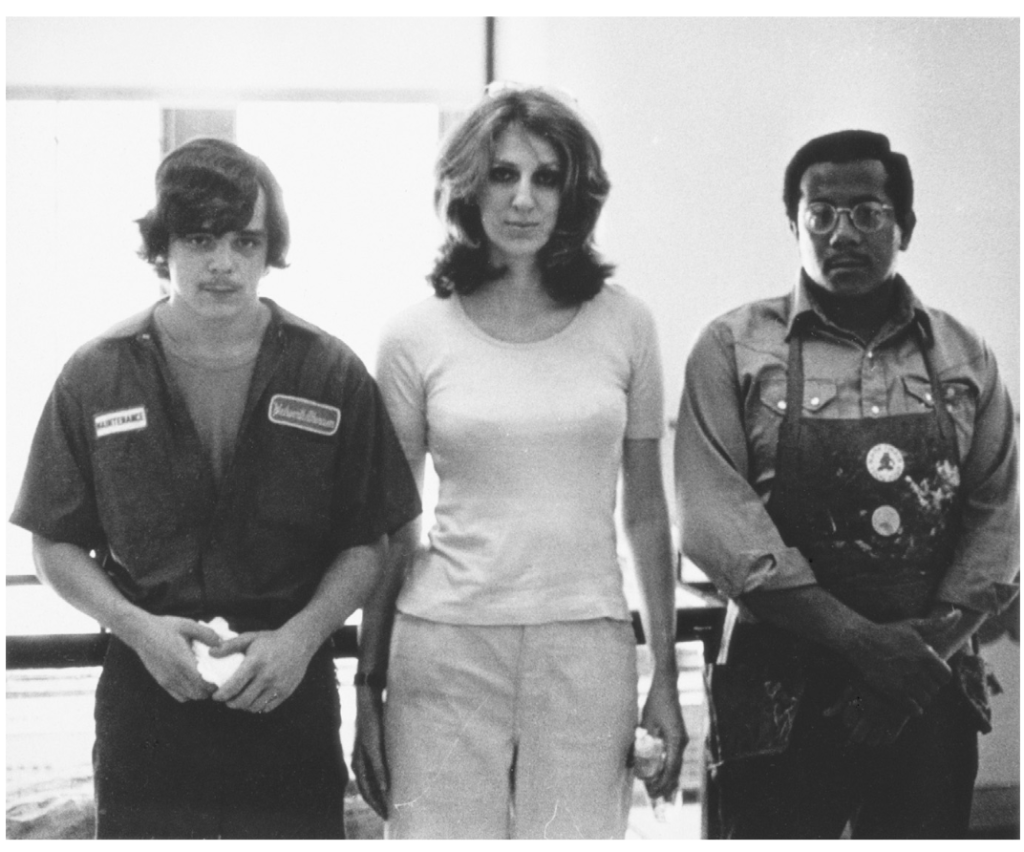

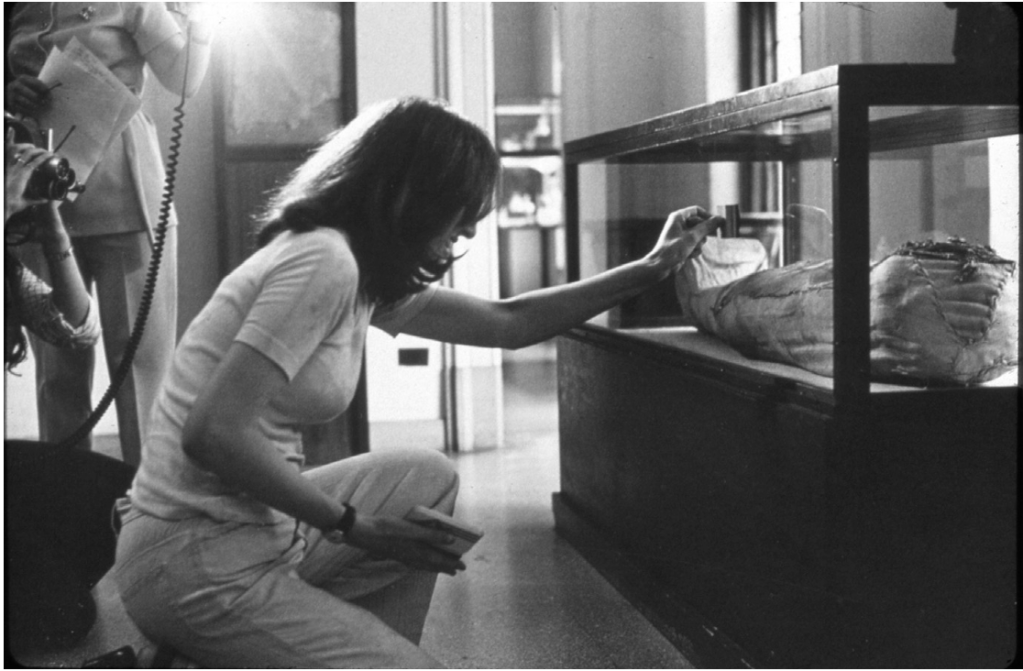

Maintenance: With the Maintenance Man, the Maintenance Artist, and the

Museum Conservator, July 20, 1973. Eleven 16 20 in. photographs, three 20

16 in., and three 11 texts. The image as published on p. 234.

Below, we’ve provided a short excerpt from her chapter, which is otherwise freely available from Taylor and Francis at this link.

The maintenance artist

Care and conservation have been the concern of many artists creating performance art, but only one called herself a maintenance artist and made preservation, broadly understood, her main goal by placing it at the center of the debate about social and feminist issues. For Mierle Laderman Ukeles, the need to preserve, to care and to maintain is crucial for an art museum—as well as economic order, society and nature—to survive. Nevertheless, in Western societies, maintenance systems have been classified as secondary to capitalist development. Being undervalued, labor, maintenance and care are usually associated with the status quo; however, they are part of a political process that could disturb power relations or, on the contrary, become malevolent systems of control. Finding this dualism socially unresolvable, Ukeles dedicated her practice to main tenance systems themselves in their social capacity, by involving this peculiar paradox rooted in the very maintenance that could simultaneously serve as a work of care and control of work.

The political significance of maintenance systems lies in the mundane necessity of support for institutions that constitute the fabric of their everyday. In her actions, Ukeles problematizes this relationship between the subject, the performance, and the object, and the systems of maintaining the shifting inter dependence between all of those factors. As conservation itself involves objects associated not only with time and space, but also bodies, politics, economics, conventions and values, it therefore plays a crucial and dual role in what Jacques Rancière called the distribution of the sensible: that is, in constituting the sensible experience of social existence, of the common, and deciding who is able to share this experience and who is going to be excluded from it as an other. The very being of political subjects is based on the ground provided by maintenance systems: care practices are normalization methods of gender, race and class roles, as caregiving work is often done by the excluded in the interest of keeping a particular vision of hegemonic order legitimized. Even personal and individual acts of care are manifestations of embodied social codes that are the subject of public debate, such as, for instance, a woman’s role as a mother within medical and legal discourses. At the same time, the need to care for oneself or for the community could create collective acts of resistance by organizing new methods of support. In this context of a Rancièrian distribution of the sensible, each decision to care is always already political. In consequence, the very performance of conservation raises questions about how the same set of gestures could be oppressive, caring and emancipating at the same time, and under what circumstances actions of preservation could be realized or reimagined. By using Ukeles’s performance as a case study, I demonstrate how the process of preservation is entangled in different political and institutional con texts, and what it means to conserve a performance about conservation.

I suggest that performance be understood not as a fixed definition but rather as a broad phenomenon. Performance is defined differently according to various disciplines: as an artistic event by theater theory, as a transfer of knowledge by anthropology, or as a work executed by the body in a manifestation of its socio-political implications by cultural and gender studies. I employ all the above-mentioned definitions to set them in mutual tension. Such an approach problematizes the relationship between the performing body and the object, especially in the context of Ukeles’s maintenance art, as care is work done in relation to something external. Does an object of maintenance activity force a work of care to stay the same or does a work of care slowly change an object in relation to a caring body? As mentioned before, there is a paradox rooted in the nature of maintenance that is distinctive to Western societies. The very paradox works through the philosophical tradition of the Enlightenment—which draws a sharp line between the subject and the object—as well as theories such as feminist new materialisms, which question this division and state that the subject is already a part of the object. Therefore, the matter is not stable but rather a dynamic process. In fact, this dynamics is crucial for feminist artists. Since the 1970s they have been working with the concept of the dematerialization of the art object (the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary) and the exploration of the female body in performance art. Within such tension, care work produces different kinds of performances in which the materiality of the object and the boundary between the subject and the object are questioned or reinforced, depending on which hegemony it serves.

…

From the perspective of relations between conservation and performance out lined above, I shall analyze Transfer: The Maintenance of the Art Object: With the Maintenance Man, the Maintenance Artist, and the Museum Conservator (1973), a performance by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who has made maintenance her ongoing social practice and investigated care as a systemic, feminist and political factor. She became a maintenance artist when she decided to refer to her daily chores as a mother (or as she described the mother’s role, a care worker) as art. The reproductive labor of women—understood as an unpaid activity reproducing the workforce by daily actions such as cooking or bearing children—was elevated to the artistic process. The transformation was expressed in the famous “Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!” in which Ukeles introduced the new language for care, as the work of support was generally taken for granted and rarely discussed at that time.7 It was a moment when the Enlightenment ration ality of the capitalist and patriarchal system was challenged by feminism. For the artist, making a caring body and its work in the domestic realm visible in a public space was the main goal. That is why in the early 1970s her maintenance practice evolved from the private sphere to the institutional one in which she executed her Transfer. I will argue that in this performance, Ukeles confronted different practices of care within the institutional realm of an art museum to see if maintenance as a repetition of labor, coded in social order and emancipation of the care work itself, could be redefined. At the same time, the longevity of her performance presents a problematic approach to its conservation, its place in art history and its relation to time, exposing some limitations of institutional critique practice, but also opening new possibilities for conservation work. Hence, I shall look back upon the production of her performance history as well, presenting the relations between art history narratives and conservation practices.

The maintenance of an art object

After reading Ukeles’s manifesto published in Artforum in 1971, the art critic and curator Lucy Lippard invited the artist to take part in the exhibition called c. 7,500. It was a travelling show curated by Lippard, in which she exhibited works by twenty-six female conceptual artists in different cities in the United States and in London in the United Kingdom. Ukeles presented several art works as part of the exhibition: a red photo-scrapbook entitled Maintenance Art Tasks that included images of her work-as-art projects; a chain attached to the album and a rag intended for its cleaning; a series of black and white photos of Dressing to Go Out/ Undressing to Go In, showing her dressing her children. She also distributed the Maintenance Art Questionnaire for the audience and artists to fill in at each and every venue and included Maintenance Art Tapes, recorded interviews with several people discussing their own maintenance tasks. Envious of her art works traveling across the country while she was working at home, Ukeles proposed to the local curators that she would perform her maintenance art as a part of the exhibition at each stop of the exhibition. For each venue, she prepared different ephemeral actions. Her first stop was at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum in Hartford in July 20, 1973, where for the c.7,500 show, she executed four performances: Transfer: The Maintenance of the Art Object: With the Maintenance Man, the Maintenance Artist, and the Museum Conservator; The Keeping of the Keys; Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside and Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Inside. Those actions were an analysis of the museum’s maintenance practices that together amounted to a critique of the art institution.

Continue reading here.

DOI: 10.4324/9781003309987-16

This chapter has been made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.