In Chapter 1 of our recently published volume, Performance: The Ethics and the Politics of Conservation and Care, Vol. 1, Pip Laurenson explores the evolving role and authority of the artist, particularly how this role shifts after the artist’s death. Performance-based artworks have transformed the practices of museums professionals, compelling them to recognize and make more visible the networks of people and technologies outside the museum that are crucial for the continued performance of these works. However, as Laurenson demonstrates, despite this shift potentially decentering the artist, the artist remains persistently foregrounded for a range of practical, systemic, and political reasons. Laurenson examines the production of performance through the lens of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of desire, which provides insight into how a performance emerges as a fluid assemblage of socio-material relations. By employing the historical concept of charisma, she further investigates how the artist’s role continues to influence the transmission of ideas central to the conservation of performance art.

Below, you’ll find a brief excerpt from her chapter. The full chapter is freely available from Taylor and Francis at this link.

Introduction

In this chapter, I look at the figure of the artist and their authority through the lens of a performance-based artwork, Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain by Tony Conrad, as an example of a complex artwork that has served to shift the practice of conservators, registrars, archivists and curators working within the art museum. This work has asked these actors, or museum workers, to acknowledge and make more visible the networks of people and technologies that operate outside the museum and upon which the continued performance of such works rely. I offer an account of the relationship between the network and the artist and seek to explore artistic authority through the ideas of charisma and desire with the aim of adding to our understanding of the transition point between the authority of the living artist and their authority after death. This chapter is written from a standpoint inside the museum, by someone who has worked with museum collections for thirty years. It acknowledges the slippery distinction between the power of the institution and the relationships held between individuals inside and outside the museum. The aim of this chapter is not to pass judgement on who should have authority in any transaction, but instead to offer one possible and incomplete account of how artistic authority operates both in relation to the social network in which it is situated, and in relation to the museum.

By inserting the idea of unconditional love into her general service agreement with the Showroom Gallery in 2019 the artist Ima-Abasi Okon planted the most powerful relational concept we have in our language into a transactional document, destabilising the relationship between the artist and the institution.3 Unconditional love suggests that one will put the interests of the other above one’s own and that nothing the other can do will lead to them no longer being loved. It starts from a position of radical generosity that is at odds with the usual transactional relationships described in legal documents. It also lays on the table the relationship between the institution and the artist, switching the discourse from a transactional concern with power, authority and control to love. The politics of the relationship between the artist and the museum and those often-invisible museum workers who work within it are complex. While recognizing the power that the museum represents, built on the foundations of a colonial system for constructing and controlling a particular imperialist narrative of history, it is also the case that within the museum artists are provided some power, albeit demarcated. For example, an acknowledgement of the authority of the artist is central to the way in which contemporary art conservation is practiced within Western contemporary art museums.4 The focus of contemporary art conservation is on learning what is important to preserve about a work and documenting that, with the intent of understanding how to fitthe work into existing frameworks and systems of documentation and care within the museum, or in some cases extending the museum’s systems and structures of care. Through their acts of care, conservators, like curators, often feel a strong connection to the artists and artwork they work with and take pride in the quality of those relationships. While practices might vary regarding the degree of support, authority and control given to artists about the care and display of their works, within standards of “good practice” within contemporary art conservation in the West, living artists are consulted and their views about conservation issues put on record through tools such as the artist interview.5 These records are subsequently given significant weight in conservation decision-making.

Although power in the relationship between the artist and the museum depends on the status, confidence, experience and often persistence of the artist, relationships with artists are vitally important. When their work is bought into a collection or loaned to a museum, it is not unusual for artists to create specifications and conditions regarding the display of their works, the use of images, restrictions on loans, and guidelines for what can be replaced. These specifications might also determine who is authorized to carry out certain activities.6 The focus in these transactions is however often on the figure of the individual artist rather than the broader social network that exists outside the museum in support of a complex work. Performance artworks are interesting because they often bring to the fore those social networks in which the artwork is situated. However, as identified in the above quotation from the field notes of Professor Harro van Lente, the foregrounding of the social network that emerged outside the museum over a number of years around Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain did not in this case diminish the authority of the artist but instead seemed to amplify it.

I consider the role of the artist in the production and persistence of a performance artwork from the perspective of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of desire as a way of understanding how a performance comes together as a fluid assemblage of socio-material relations.7 Desire helps us to understand the motivating force for the assembling of the network, and charisma is the force that draws people to join the network. My account attempts to provide an explanation as to why a shift in focus to the networks of people and technologies that operate outside the museum does not act to decenter the artist, why the artist has remained persistently fore-grounded. I draw upon the historical concept of charisma to understand how the role of the artist continues to operate within the ideas of transmission that are central to the conservation of performance art.

Charisma is capable of eliciting love. The centrality of the artist and the authority given to them by contemporary art conservators in their practice has been pointed to by those from other disciplines, such as anthropology, as somewhat blinkered and limiting, creating what is seen as a blind spot within contemporary conservation practice.8 As the two quotations that open this chapter, one from Ima-Abasi Okon’s General Service Agreement and the other from the fieldnotes of Professor Harro van Lente indicate, the relationship between those supporting the artist and their work might have more in common with unconditional love than is commonly found appropriate in relation to the objects of study in the academy. The exploration of desire and charisma, therefore, also provides us with an alternative account of the relationship of those who are responsible for the care and stewardship of artworks to the artist and their artworks, which is so often simply read as naïve or sycophantic.9

Live performance in collections

Live performance art has caught the imagination of conservation and those within the museum concerned with the stewardship of collections. While I do not want to perpetuate binary thinking about the material and immaterial, these works bring to the fore a consideration of transmission over time and between generations. To claim that a performance work can be passed on from one person to another and to persist or remain is to evoke the debate about the ontology of performance with some, most famously Peggy Phelan, arguing that: “Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so it becomes something other than performance.”10 Whereas others, such as Rebecca Schneider, have argued against the equation of performance with disappearance. For Schneider this amounts to the privileging of the document over other types of knowledge, a privileging that has its roots as a tool of empire to undermine local knowledges and present memory as having failed.11 When works come into the museum, a judgement has already been made that these live works can be repeated and performed again and again over time, as a fundamental condition of an artwork becoming a museum object.

To understand the ideas of transmission at play it might be useful to consider a couple of examples. One of the first live performance works to come into Tate’s collection was Tino Sehgal’s This is Propaganda, 2002. Sehgal, as part of his practice, insists that there be no material remains from his works. He therefore does not allow the work to be recorded, photographed or documented, resisting these standard museum technologies. Instead, he requires that the work is remembered and transmitted using “body-to-body transmission,” pointing to a tradition in dance, for example, where one dancer teaches another the dance through physically practicing, copying, or perhaps physically correcting the bodily movements. This stands in contrast to transmission through documentation and challenges the museum to learn new ways of thinking about memory. Of the live works which started to enter Tate’s collection in 2005,12 some performance works operate in ways that make them simple to care for— such as delegated performances activated from simple instructions.13

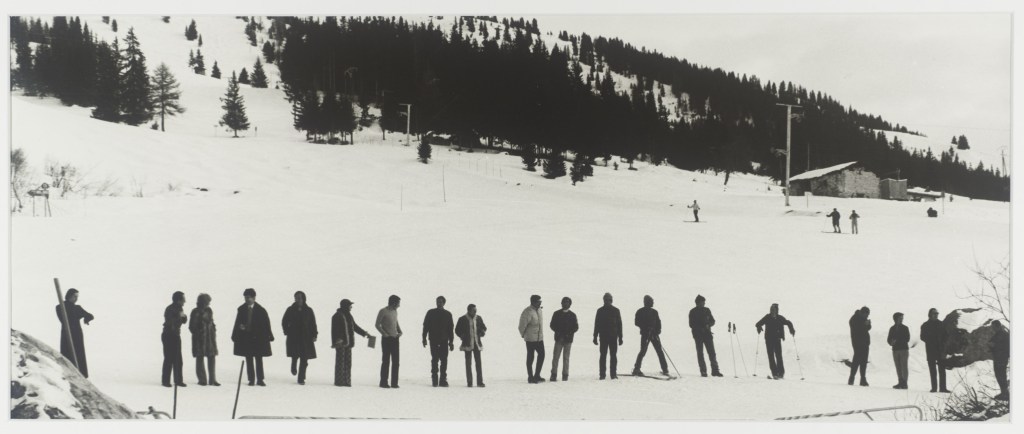

The artwork Time (1970) by David Lamelas exists in Tate’scollectionastwo manifestations, each with their own accession number. One is a silver gelatin photograph and the other is a live performance work. The photograph documents the first performance of Lamelas’s Time 1970 in the French Alps (Figure 1.1). The instructions for the live performance work are simple and flexible: a group of people stand in a line; the first person tells the time to the next person; they “receive” the time and “hold on to it” before announcing it to the next participant; the last person announces it “to the world” in the language of their choice. The work has been performed in numerous locations, from outside in the French Alps as shown in the photograph (Figure 1.1) to the Turbine Hall in Tate Modern (Figure 1.2) to recently being performed on Zoom and live streamed on YouTube in 2020 (Figure 1.3). The performance of the work has also adjusted to the different devices for telling the time, from wrist watches to mobile phones to computer clocks.14

Other forms of performance are more complex, less flexible and easy to steward and “update.” Instead they push up against the structures and definitions of the museum, asking fundamental questions, not only about how much improvisation, indeterminacy, change and fluidity are possible for a collected artwork but also how the museum is to maintain such a work within a structure designed to keep objects and to keep them the same.15 These artworks serve to reveal the tools and structures of the museum and our practices that have been honed over the centuries in the mission to render artworks in the art museum static, and independent from ongoing practices of “making” that might come from continued dynamic and physical engagement with the artist and their context. The limited efficacy of the standard rhythms of display within the museum for works that require memory and body-to-body transmission are highlighted by the display cycle of Sehgal’s This is Propaganda. Since entering the Tate’s collection in 2005 it was shown in the Tate Triennial at Tate Britain in 2006 and then not again until it was part of BMW Tate Live at Tate Modern from June 17–19, 2016. It has not been shown since, but let us imagine that the next time the work is displayed might be in 2026—is a ten-year cycle frequent enough for the memory of the work to be effectively transmitted?

Unlike This is Propaganda there are no restrictions on documenting Conrad’s complex performance work Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain, 1972. Unlike Lamelas’s Time, Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain did not come with a score, in fact Conrad was famously anti-score.16 Instead, Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain sits somewhere in between, in that the conservation strategy has been to create a document—a dossier of text, image, audio and video and also to recognize the importance of person-to-person transmission and acknowledging the knowledge held by the social network that surrounds and supports the work, and which exists outside the museum.

Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain is a live 90-minute work that was first performed at the experimental arts venue The Kitchen in New York in 1972. While the work has within its life been performed in different configurations, at Tate Liverpool in 2019 it was performed with one violin live and one recording of Conrad playing the violin, a bass guitar, a long string drone (an instrument invented by Conrad) and four film projections. During the 90-minute performance the four film projectors project an image of black and white vertical stripes which very slowly come together as one square. Towards the end of his life, Conrad had devised a form of the work where his violin part could be replaced by a recording of him playing on a loop. This was used when he was not well enough to perform. While alive Conrad was central to the teaching of the work prior to a performance, travelling to the venue a few days in advance and creating a social connection with those involved. Accounts tell of Conrad’s sociability, that he enjoyed spending time with young people, was happy to join or suggest a party. As the curator Maria Palacios Cruz recalls, when he came to perform Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain at Paleis voor Schone Kunsten organized by ARGOS in Brussels in 2007, “he was the sort of person you could easily meet and spend a really fun evening with, feeling, maybe, a closeness. I think everyone felt close to him.”17 Lectures often accompanied his performances and to all accounts these were very funny. In talking about an introduction that Conrad gave to a performance at Café Otto Maria Palacious Cruz recounts “the way he did it, in a way, I guess, transforms theaudienceintofinding it all very funny, or accepting it or opening it up, or not finding things hermetic or difficult. So that’s the thing. … [I]f you see his work without him, his work is very dry.”18 During our research, it was not uncommon for our requests for information from past performers of Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain to end with comments such as “ Tony was the nicest guy you could imagine!”19 Conrad created a close connection with people during these performances of his work, extending the network of those who cared for the work.

My first encounter with Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain as a collection care specialist and a conservator was a performance of the work in the Tanks, a performance space in Tate Modern, on January 18, 2017, approximately nine months after Conrad’sdeath.20 Thanks to the foresight of the curators Andrea Lissoni and Carly Whitefield, this performance provided a moment to bring some of the network of people that surrounded Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain together to co-create the way in which the work might continue without Conrad’s presence as its primary instigator, transmitter, teacher and first violinist. There was therefore no doubt that in order to think about how this work might enter Tate’s collection we needed to consider and develop an understanding of that social network and its evolving role in sustaining Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain.

Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain formed the first work to be studied as part of the research project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum. The aim was to build and test a dossier of images, text, video and audio that would form the basis of information to be provided to new performers of the work. This had been compiled by Time-based Media Conservation in consultation with the artist’s estate, headed by the artist Tony Oursler, Andrew Lampert, the archivist of the estate, and previous performers and collaborators with Conrad. The new performers of the work had arrived at Tate Liverpool a day early to rehearse before they performed the work to a small, invited audience who gathered after the performance. In the center of those who gathered after the performance were those who had performed the work before with Conrad, some more than once. These are the “transmitters” of the work. With them were the new performers who had just played the work live for the first time. Gathered around them were conservators, curators, registrars, technicians and two academic observers.21

The conversation examined what had been conveyed and what had been lost in the transmission of this work through the dossier, with the exchange focusing on the “embedded know how” of those assembled. One of the transmitters read from notes she found about her experience of playing of the piece: “My arm hurt, I wanted to stop but I was so worried that if I did I just wouldn’tbe able to start again.” After all the preparation—the readying of equipment and prints; the assembling of spaces, and people; the testing; the shipping; the building; the unpacking; the tuning of instruments; the checking; the documenting the performing of all of these practices—demonstrated the close attention to the specificity of the human and non-human material that makes up this work. While the week culminated in a second performance of the work, this time for the public (see Figure 1.4), what had also been performed was conservation as a social activity involving people and things which extend beyond the museum.

Performance artworks sit well with the direction of travel of contemporary art conservation in that they bring to the fore the social and the relational nature of conservation, raising the question of the performance’s ability to exist beyond the presence of the artist and also bringing different ways of knowing and epistemic cultures such as those from dance and theater into the museum. Performance artworks, perhaps more than any other complex artworks, make visible the reality that artworks are situated within networks or assemblages of human and non-human agents which are essential to their realization.22

The artist and the museum

The figure of the artist in the contemporary art museum has in many ways been untouched by a decentering of the artist in academic discourse, particularly within literary criticism. Take for example Roland Barthes’s claim that the construction of the author is essentially an expression of a bourgeois ideology where the creator is seen not only as an individual but as a determinate and fixed source of works of art, possessing privileged access to their meaning.23 This challenge to the artist as individual creator claims that artistic production is collective, that it reflects the social structures in which it operates and also that artworks are co-created by the audience.24 Janet Wolff notes that as theory continues to decenter the subject and displace the artist as creator, popular culture seems to increase its interest in biography. Similarly, the artist continues to be a central figure within the contemporary art museum and its conservation practices. While relationships with artists are widely recognized as essential for successful curatorial practice, the importance of these relationships within conservation practice is often underacknowledged and rendered invisible within the art museum. In part this is because to make these relationships visible wouldbetochallenge theepistemic hierarchies and delineation of roles. However, there are examples of recent initiatives that have served to make the relationships and working practices of collaboration between artists and conservators more visible. For example, the modern and contemporary art museum SFMOMA (The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), in the reopening of their museum with the new wing designed by the architects Snøhetta in 2016, championed a vision of the artist at the center of the museum, creating dedicated spaces for collaborative work between conservators and artists. The framing of conservation as a practice of care also foregrounds relationality where the artist, the artwork and an existing network of care surrounding a work can all become part of a focus of that care.

Within the West, despite the biographical artist and their intent being the dominant way in which the artist is portrayed within the art museum, any wish to decenter the artist to align with developments in literary theory is done against a backdrop of knowing that the place of the artist within the contemporary art museum has been hard won through its own political struggle. A defining moment in this history was the founding of the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC) in 1969 prompted by protests surrounding the removal by Takis (Takis Vassilakis) on January 3 of his work Tele-Sculpture (1960) from the exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age at Museum of Modern Art in New York. Although the work was in the museum’s collection, the artist had expressed his wish for the work not to be included in the exhibition on the grounds that it did not represent his most recent work. The AWC was not the only group of artists protesting against museums at the time,25 however it was a high-profile group that demanded not only more rights for artists over their works but also greater representation of Black, Indigenous and women artists.26 While museums still control when a work is exhibited and largely in what context, in the intervening years legislation both inthe US andinEuropehas afforded greater rights to artists.27 While large institutions of course hold far more power than any individual artist, and scandals regularly occur when museums overlook artists’ wishes, this is not inconsistent with many individuals within museums being mindful of the power of the institution and working to accommodate an artist’swishes.

The concept of “artist’s intent” has been central within contemporary art conservation, supported by practices of the artist interview28 and the acknowledgement of engagement in dialogue regarding the care of works in a collection that can span many years. Although unusual in her engagement with the museum, the artist Ima-Abasi Okon’s interaction with conservators during the installation of her works, as part of the spotlight display at Tate Britain in 2021, is a case in point. Okon’s relationship with the conservators Jack McConchie and Libby Ireland was developed over a number of months during which time Okon wished to understand and learn more about their practice while the conservators sought to understand what was important to the installation and conservation of her works. Okon did not however want to be recorded, as is standard with conservation interviews, resisting the practice of fixing. Also, Covid-19 restrictions prevented some of the testing that might normally happen with a new work before it went into the gallery to establish the boundaries of the configuration of the elements. The time installing the work was therefore key to understanding how to care for the work, moving this process into a more informal space where a relationship of mutual trust could be built.29

This partial and hard-won authority gained by artists is made murky by the persistence of the modernist figure of the artist.30 For example, one only needs to look at the standard output in promotional and educational videos by our major art institutions to see the tropes of the lone artist in the studio repeated and promoted.31 On the whole monographic exhibitions do better commercially than group or thematic exhibitions, focusing as they do on a singular artist and often incorporating extensive biographical material. While the museum might be aware of some of the problematics in the way in which the figure of the artist is thought about, it is true that the art museum is out of pace with academia in its construction and analysis of the figure of the artist. While the experience of practitioners within the museum points to a more collective notion of artistic production, it has proven difficult to separate the museum messaging from the image of the sole artist genius which also underpins the logic of the art market.

The respect shown to artists is also entangled with a desire from those working within the contemporary art museum to find a place of hospitality for the artists with whom they engage within structures and systems which are sometimes at odds with that desire.32 Ima-Abasi Okon, in the quote from her General Service Agreement that opened this chapter, adds love as well as pay, recognition and representation into the demands of artists in the twenty-first century.

Continue reading here.

DOI:10.4324/9781003309987-3.

This chapter has been made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND4.0 license.

Notes

1 Fieldnotes of Professor Harro van Lente, observing a feedback session where, as part of the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, we were working on the transmission of Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain at Tate Liverpool in 2019. Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum is a three-year project funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation that works to develop both theory and practice around artworks which challenge the structures and definitions of the museum. The project involves researchers from across conservation, collection management, archives and records and curatorial within Tate. Tate, “Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum,” Tate, accessed October 11, 2021, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/reshaping-the-collectible.

2 Ima-Abasi Okon, “General Service Agreement between Ima-Abasi Okon and The Showroom Gallery,” in ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ (Press for Practice, 2019), 3.

3 Okon, “General Service Agreement,” 3.

4 For example a pivotal concept for contemporary art conservation is that of “artist intent” which conservators seek to understand or decipher through tools such as the artist interview. The artist interview in conservation records the artist’s attitudes to change and often acts as a guide, and sometimes as a means of authorizing, particular conservation strategies. For a discussion of artist’s intent in conservation see Glenn Wharton, “Artist Intention and the Conservation of Contemporary Art,” in Objects Specialty Group Postprints, ed. E. Hamilton and K. Dodson, 2015, 22: 1–12.

5 For a discussion of the artist interview see Fernando Domínguez Rubio, Still Life: Ecologies of the Modern Imagination at the Art Museum (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2020), in particular chapter 1.3, “The Modern Subject of Care,”, 116–144.

6 For example, Bill Viola’s Five Angels for the Millennium (2001), was acquired withvery detailed specifications for the display space, the quality and dimensions of the images, the positioning of the entrances and exits, the lighting and the acoustics. Artists often authorize one official image of their work and are very precise about how the image is cropped, etc. An example would be the authorization of the use of one image for James Coleman’s Charon MIT Project, 1989. The artist Phil Collins has specified that the 2004 work they shoot horses cannot be shown in Israel or the USA without permission of the artist and Tania Bruguera has specified that Tatlin’s Whisper #5 (2008) can only be performed in a location that has experienced civil unrest and protest and where the police control crowds using horses. The long string drone acquired with Tony Conrad’s Ten Years Alive on the Infinite Plain can be replaced and part of what was acquired were the instructions for its fabrication. Sol LeWitt and his estate specify to the owners of Sol LeWitt works who is authorized to create his wall drawings.

7 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 1987).

8 Part of the motivation for this chapter were conversations with Professor Haidy Geismar during her Fellowship at Tate as part of the project Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum.

9 For accounts of the role of love in relation to museum practices see Emily Pringle, “Art Practice, Learning and Love: Collaboration in Challenging Times,” (London: Tate, 2014), http://www.tate.org.uk/research/research-centres/tate-research-centre-learning/working-papers/art-practice-learning-love, accessed February 27, 2021, and Anthony Huberman, “Take Care,” in Circular Facts, ed. Mai Abu Eldahab, Bina Choi and Emily Pethick (London: Sternberg Press, 2012), 9–18.

10 Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London/New York: Routledge, 1993), 146.

11 Rebecca Schneider, “Performance Remains,” In Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History, ed. Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 138–50.

12 Tate was the first contemporary art museum to acquire live performance when it acquired Tino Sehgal’s This is Propaganda (2002) in 2005 and Roman Ondak’s Good Feelings in Good Times (2003) also accessioned into the collection in 2005.

13 “Delegated performance” is Claire Bishop’s term for performances that are carried out by someone other than the artist. Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (New York: Verso Books, 2012).

14 Time (2020) and Time (1970) are not considered by the artist to be one work that has evolved over time. Instead, David Lamelas considers Time (2020) to be a new work, as the although the two performances can be seen as quite similar, the medium and the context are different. Personal Communication with the gallery Jan Mot, September 24, 2022.

15 See Domínguez Rubio, Still Life, for an examination of mimeographic labor in the museum and Fernando Domínguez Rubio, “On the Discrepancy Between Objects and Things: An Ecological Approach,” Journal of Material Culture 21, no. 1 (2016): 59–86, for a discussion about how the museum maintains an artwork as legible as the same work over time.

16 “Hans Ulrich Obrist: Brandon Joseph…argued that you seek to annihilate the idea of the score instead of realizing it. Tony Conrad: Annihilate, yes. My idea was to eliminate the social and cultural function of the score as a site. As a cultural site altogether. Period.” Hans Ulrich Obrist and Lionel Bovier, eds., A Brief History of New Music (Zurich and Dijon: JRP/Ringier and Les Presses du Réel, 2014), 194.

17 Maria Palacios Cruz, interview by Lucy Bayley, Pip Laurenson and Hélia Marçal, August 10, 2019.

18 Maria Palacios Cruz, interview by Lucy Bayley, Pip Laurenson and Hélia Marçal, August 10, 2019.

19 Stefaan Quix, “Tony Conrad – Brussels,” email exchange with Dr. Lucy Bayley, December 13, 2021.

20 Conrad died on April 9, 2016.

21 One of these academic observers was Professor Harro van Lente whose quotation from his field notes opens this chapter.

22 My thinking is here influenced by a lineage of thinkers starting with Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), which was first introduced into contemporary conservation theory by Vivian van Saaze in her book Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artworks (Amsterdam: University Press, 2013). See also Jane Bennett’s description the agency of assemblages and “thing power” in Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (London and Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2010), chapter two. Also important in this space is the work of Donna Haraway, in particular Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991). Picking up this work through a focus on care is María Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

23 Roland Barthes, “Death of the Author,” in Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (London: Fontana, 1977), 142–48.

24 Janet Wolff, The Social Production of Art (London: Macmillan, 1981): 118.

25 See Francis Frascina, Art, Politics and Dissent: Aspects of the Art Left in Sixties America (Manchester University Press, 2008); Rebecca Deroo, The Museum Establishment and Contemporary Art: The Politics of Artistic Display in France after 1968 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

26 For the Art Workers’ Coalition’s complete Statement of Demands from March 1970, see “ART WORKERS’ COALITION: STATEMENT OF DEMANDS,” accessed October 10, 2021, http://theoria.art-zoo.com/art-workers-coalition-statement-of-demands.

27 For example, the adoption in the US of the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 was the first federal copyright legislation to grant protection to the moral rights of artist. In the UK the Copyright and Designs and Patents Act of 1988 also added moral rights of integrity and attribution.

28 Examples of the literature on artist intent include Steven W. Dykstra, “The Artist’s Intentions and The Intentional Fallacy in Fine Arts Conservation,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 35, no. 3 (Autumn – Winter, 1996): 197–218; Rebecca Gordon and Erma Hermens, “The Artist’s Intent in Flux,” CeROArt. Conservation, exposition, restauration d’Objets d’Art, no. HS (September 11, 2013); Nina Quabeck, “The Artist’s Intent in Contemporary Art: Matter and Process in Transition” (PhD diss., University of Glasgow, 2019), https://theses.gla.ac.uk/75173; Glenn Wharton, “Artist Intention and the Conservation of Contemporary Art,” Objects Specialty Group Postprints, vol. 22 (2015): 13. In terms of practice within museums, consider for example the new spaces within the design of SFMOMA called the Collections Workroom that supports collaborations between artists, scholars and the museum staff. See “The Artist Initiative,” accessed October 11, 2021, http://www.sfm oma.org/artists-artworks/research/artist-initiative.

29 For an account of their work with Ima-Abasi Okon see Libby Ireland, “Learning through the Acquisition and Display of Works by Ima-Abasi Okon: Enacting Radical Hospitality through Deliberate Slowness,” Tate Papers, no. 35, 2022, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/35/learning-through-acquisition-display-works-by-ima-abasi-okon-enacting-radical-hospitality-through-deliberate-slowness, accessed January 29, 2023; and Jack McConchie, “‘Nothing Comes Without its World:’ Learning to Love the Unknown in the Conservation of Ima-Abasi Okon’s Artworks,” Tate Papers, no. 35, 2022, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/35/learning-to-love-the-unknown-conservation-ima-abasi-okon-artworks, accessed January 29, 2023.

30 For a detailed examination of the conception of the modernist artist, see Caroline A. Jones, Machine in the Studio: Constructing the Postwar American Artist (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

31 Consider, for example, the video outputs from Tate Shots many of which focus on the artist in their studio. An example is “Maggie Hambling – ‘Every Portrait is Like a Love Affair,’ Artist Interview, Tate Shots,” 2018, accessed October 11, 2021, https:// youtu.be/M4-4Syn1pmE.