In this essay, our visiting researcher Felipe Ribeiro challenges the tendency to view performance art primarily through its afterlives—documentation, restaging, or institutional preservation—and instead advocates for recognizing its endured life as a continuous, open-ended process shaped by accumulation, incompletion, and relationality. Using the evolving project Common Ground as a case study, the author proposes performance as a living, transformative practice that resists fixation and invites ongoing negotiation, collective participation, and speculative engagement. Rather than treating performance as something that ends and is later remembered, the text calls for practices that sustain its vitality and presence across time and contexts.

“Life is a rough terrain.”

Kathleen C. Steward

The afterlives of performance. The term has gained especial relevance on the verge of this century as performance art makes its way to museums’ collections and solicits new considerations of maintenance and conservation. The issue, however, precedes institutional needs, and can be drawn back to performance’s very blueprint ability to make things happen, thus, foregrounding experience rather than display. After a performance, what there remains to be seen? Not by chance the presence-absence binomial has heated up performance’s scholarship questioning the effectivity and the limits of its documentations. If ontologically we may affirm an image of a performance “[ce] n’est pas une performance”, I propose we invert the logics and think the other way around: If performance is available just in the actual physicality of its happening, doesn’t it become deemed to melancholic, nostalgic, and lacking approaches of always belated accesses through its afterlife?

As a performance researcher and maker, I’m hoping to contribute with such a discussion perhaps by, if not giving it a step back, simply allowing performance to persist a little longer where it stands, i.e. not jumping in so quickly to its afterlives but remaining in its less discussed endured life, which, I will argue, is sustained in the accumulation of different activations. Diverging from the logics of staged theatrical or dance pieces structured and performed repetitively during seasons and tours, the endured life of performance may point to a more radical development, one that does not cast the event as completed in itself, thus able to be reproduced in different occasions. I’m hoping that such an approach may make of performance (and not only its documentation) an ever-incomplete display, a contingent share exceeded by both past and yet to come experiences. As a field of practice and study emerged within the intricacy of art and life, I suggest, performance resists starigh foreward definitions. It ought to be perceived through the considerations of what is a life, in all its vitality, intensity, changeability, and the incompleteness of accumulative activities and experiences. All of which may, eventually, lead to its afterlife.

My aim here, therefore, is not to deny the afterlife of performance nor simply substitute it with a new expression, but to fight the automatism that may deem life too punctual, too contingent, and too fixed as if it were deadlocked in the short instance of a happening encapsulated in itself and ready to, as soon as it is over, be quickly upgraded to an afterlife devoted to its restorative freer flow of “eternity”. Whenever the afterlife of performance is framed, a position towards its life is assumed. My position is that performance’s lifespan should be perceived according to each work’s own developing singularity. Hopefully the more we acknowledge it, the more the life of performance works can be endured and nurtured. How do we invite makers and institutions to an endured approach to performance? And in that case, once we accept it exceeds its initial happening, what does performance become, then?

These considerations are directly linked to the development of Common Ground, an ongoing project that I initiated in 2020 during the residency program “Naked Transitions” at Gessnerallee in Zurich. I first held a public talk on soil, my interest in its slow morphological changes and migrating drives, then translated into collective artistic engagements. I proposed to the resident artists that we build our common ground by bringing in artifacts that somehow enhanced our sense of collectivity. The objects were not meant to be inserted into our everyday group dynamics; on the contrary, they were to be withdrawn from their usual functionality and covered with layers of clay, which gradually accumulated into cubic forms. Common Ground would then progressively become an entity that is both the sum and the emanation of everyone’s efforts, decisions, and material contributions.

Throughout two weeks, the group of twenty participants responded to my call and chose, each, different artifacts to mingle in layers of clay. Whether due to personal or political reasons, or through randomly collected materials in strolls throughout the city, the volume piled up. Some of the materials, however, had inscribed ecological concerns that needed to be unpacked. For that, the group gathered in a conversation that evolved into a 3-hour assembly, imagining the pros and cons of laying Common Ground underground, due to it containing inorganic matter. Provisional agreement was reached once we set a six-month time frame within which to dig out those inorganic remains. That two-week performative proposition led to a promise. Months later, the failure of it coming to facts turned what was supposed to be just an addendum to the performance into an open-ended situation that reframed its own duration.

Common Ground helps us to situate what we mean by the enduring life of performance, or even better it helps us to define it by de-situating performance, since its progression is shattered in time and space, precipitating enmeshments of different sites and accumulations of different developing stages. As a performance that entails each participant’s input, depending on each’s own impulse and pace, and progressing through different decisions which will then unfold new sets of problems, Common Ground poses issues to witnessing. Many moments happen through direct involvement, and we hardly know what’s there to be seen. Still, whenever audience is present, they do not witness the work unabridged. That’s for performance doesn’t occur only when on display, it occurs imbued of making things happen, and I’m interested in when its experiences surpass and question spectatorship as an ability.

That created volume can’t be clung onto either. As much as it’s endowed with an aura due to the uniqueness formation out of care of participants, it still functions more as a means than performance’s own end. It’s valued for all that it is, a becoming-ground that brought us all the together and through which concerns were raised, and imaginative landscapes were generated both on futurity and our current relationship with the environment. Its concrete existence works as a propulsor and a catalyst of a conceptual, material, provisional, and projective diagram balanced by negotiations of forces. Therefore, following extensive scholarship already produced on the topic of performance and relics, Common Ground accounts for generative operations in all their choices, doubts, decisions and gestures, which are not sufficed by that volume itself, although it stands as one element of that performance.

I’m also interested in how its invisible existence laying underground highlights the degree of imaginative and speculative drives imbued in performance. I’ve been calling it an invisible sculpture. While making itself present while absent, and absent while present a speculative flow is generated and in regard to its very condition: the imprecise location of its burying, and its current process of ageing and decay. It fascinates me to think that soil migrations which were the conceptual trigger for its making in the first hand, are now physically responsible for its degeneration. Shattered and weathered, imprecise but existent, that underground invisible sculpture embodies conditions of incompleteness that helps us to negotiate senses of the actual with perceptions of the indexical.

As a field emerged amidst experimentations with the dematerialization of the object of art, performance may happen through objects but never concede fully to objecthood. Same wise, it may count highly on prompting concepts, but it’s arguable if they can take full account for its actual making. In fact, if we are dealing with the so-called performative programs, they will definitely request embodiment to live up. In the words of Eleonora Fabião, “a program is a motor of experimentation because its practice creates body and relations between bodies. It triggers negotiations of belonging. It triggers affective circulations that were unthinkable before the program’s formulation and activation.” (2018:59) And also: “Once enacted, a program deprograms organisms and ambience.”[1](2008:237)

Performance has been a hard instance to circumscribe. To consider it by its enunciation or objectual remains may seem reducing. Meanwhile, accepting its inherent immediacy as a radical coefficient of presentness may prove reductive as much. How does one defy that immediacy without falling into the luring pitfalls of totemization? Perhaps that’s when the intensive and evolving thread of accumulated events comes as a means of performance’s endured life. It’s then neither about conceding performance to objecthood nor necessarily complying its boundaries with that of a completed task, but living through incompletion, and under an enhanced hearing of how to keep moving through and with the work.

In that sense, the failure of digging the in-organic material out of the soil is informative. The two ethical facets of that performance one ecological, and one of trust become explicit and will both play an important part in the continuation of Common Ground. As I left the searching site, my discontent suddenly raveled into a new quest, turning the lack into a call for compensation. How to work through that call, though, was not up to me to decide alone. And in the impossibility of bringing that same original group of participants once again together, the quest had to find other collaborators to endure. Common Ground, then, evoked a new materialization, the lecture-performance format through which all chain of events engages into a storytelling narrative and end up by gathering the audience into a new assembly. It became up to each new group then, to come up with a concrete action, however provisional and insufficient it may be, to make up for the ecological and trusting failures of my searching for the lost inorganic remains.

Common Ground weaved the memory of its previous constituency to the enactment of new developments. More than aiming at giving full account of that inaugural event, the lecture-performance is a way to keep up with its problems, to address them forward, and to bifurcate them in different directions. I’ve been each time more convinced that one of the great contributions of performance art lies in its generative forms of “staying with the trouble”. With Common Ground, it is, hence, not different. As a strike of luck, the first held assembly has agreed that the lecture-performance should be carried on for, at least, twelve times. An agreement that committed the work with duration. As I write this text, it’s been enacted four times already. The latest one at HKB – Bern University of the Arts, and it was the first time that the materiality of the lecture-performance, with all its text printed on paper were assembled to other artifacts and ended up buried in a public lawn in the auditorium’s whereabouts. Dirt from that site was then collected to be used in Common Ground’s next activation. The public activations intermitted to resting moments of withdrawal, while decay of – now more than one – invisible sculpture – proceeds, points to a endured life of shimmery access to facts. Even when Common Ground is not shown, it literally continues existing underground, its problematics remain in the air, the work returns and haunts, its troubles active, its life surpassing each single event.

I use the word endure purposefully as it usually lends its name to performances that request resistance both from performers and audience within one happening. I propose, however, that endurance may also be materialized in intermittent activations of a performance’s persisting life. Across time it may call for a sense of repetition that is less supported by reproduction and further fostering accumulation.

Attuned to the interplay of performance and conservation, and while critical of the idealizations of reproduction, Diana Taylor distinguishes archive from repertoire. In general lines, she worries that the archive lays on the bottom of locked drawers of massive institutions mostly kept inactive and hardly accessible. That’s in the name of an enhanced sense of material preservation which paradoxically withdraws them from life. She then confronts these forms of “frozen” existence, to repertoire, a necessarily embodied, performing practice of living archives. The applicability of repertoire to the performing arts feels rather direct through restaging, reenactments, and choreographic transmissions, each embodied under the risks of the real. Confronted with her perspective on archives, the myriads of possibilities within embodiment antipodes to the analyzes of staged performances solely by their textual scripts or choreography. This clash is poignantly acknowledged by Marcia Siegel when stating that often “it is the dancers who disappear when their dancing is turned into written history.”(apud Burt 2004:4)

An important step forward on behalf of the liveliness of events, repertories develop from a sensible approach to the notion of restored behavior, a term conceptualized by Richard Schechner and Victor Turner to scrutinize how performance performs in similar patterns of culture and language, in their negotiating degrees of repetition and difference. For that matter, repertories work with transmissible conventions that reference past events in their bringing back to life. Properly functioning as an afterlife, repertoires seem to frame spectatorship through a set of fractal lenses, one in which the notion of time actively overlaps asynchronous spaces, allowing in the least the spontaneity of the actual event to be blurred by the haunting envisioning of the circumstances in which it was conceived. Thus, repetition usually plays a much stronger and definitive role in repertoires, one that has mostly to cope with difference.

To endure the life of performance instead to its afterlife one needs to find other equations and operations, some that instead of formally mirroring a past event, challenge itself to go through the looking glass, welcoming the power of distortions and diffractions, and proactively working with them. Whenever this happen, difference is nurtured and not just coped with. It’s in that sense that I’d suggest we move pass restoration as a goal to pave the way towards accumulation. Performance then is no longer taken as a fixed completed entity ready to be repeated but accepted as a living being in its development and incompletion.

Accumulation and incompleteness have powered Common Ground on. As much as restorative behavior attunes to perpetuation, it also alludes to maintenance by some degree of similarity. Accumulation, on the other hand, becomes a way to carry further, to develop, to unfold by asking what’s next. It also assumes performance as un-fixed and incomplete. Not because it lacks anything but because it’s a sum. I’d assume that intuitively that’s what was the performative carried on by Common Ground when the lack was turned into a quest for always provisional compensations.

I wonder and hope that the more Performance’s endure in their lives the more we are invited to access it through different, changing angles. In that case, Performances are not lacking and offering belated access. Instead, they are framed within circumstances that invite us to experience however presence while filling in the past and prospecting new landscapes yet to come. Hopefully that will make not only certain performative works to persist, but in doing so we’ll be advocating for the persistence of performance as a fleeing ability to keep reinventing itself and its relations to the world, the artworld included. Afterall, performance emerged at a time when art faced a highly experimental trope, defying its long-lasting support on representation, hence resisting commercial trade within an established art market. By then, one important way to defy the standards of art production was to find its own means of dematerialization by not sufficing to the standards of objecthood, that which can be owned, collected, traded, kept – Allan Kaprow’s happenings and activities being exemplary. Now, as the selling of experiences has become the new institutional trend, performance needs to review its blueprint once again. As a field nurtured by the awareness of its context, situation, and the fight against automatism, I suggest that as much as it hasn’t conceded to objecthood, it must also surpass eventhood, a way to do so might be affirming the intangibility of its existence as an undergoing living and enduring phenomenon.

REFERENCES:

Burt, R.(2004). Undoing postmodern dance history. Available at http://sarma.be/docs/767 . Accessed on June 2nd, 2025.

Fabião, E. (2018). Call Me Text, Just Text*. Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 19(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2018.1421304

Fabião, E. (2008). Performance e teatro: poéticas e políticas da cena contemporânea. Sala Preta, 8, 235-246. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2238-3867.v8i0p235-246

Taylor, D. (2003). Archive and Repertoire. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822385318

[1] In the original: “Ao agir seu programa, des-programa organismo e meio.”

Watch Felipe Riberiro’s lecture performance “Common Ground,” which he presented in April 2025 within the research seminar series “Research Wednesday” at the HKB Bern, at this link.

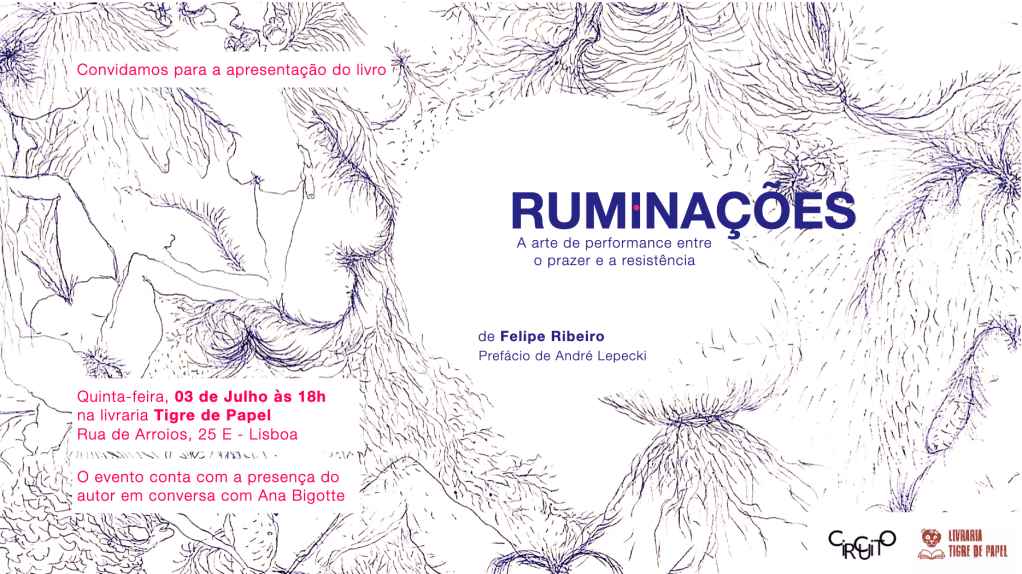

Felipe’s book, Ruminações: a arte de performance entre o prazer e a resistência, originally released in Brazil in 2022, has now been reedited and published in Lisabon. The book launch takes place on July 3rd at 6pm at Tigre de Papel Bookstore, in Lisbon.

In the words of André Lepecki who wrote the foreword of the book, Ruminações translates to Rumination, and it is with this action that links thought and digestive system, reason and animality, that Felipe Ribeiro proposes an urgent theoretical, affective, artistic and political construction of what could be a new ethics and a new aesthetics of performances if they were seen through the lens of a desire that is first and foremost visceral. With the viscera mobilized into thinking, a whole minority scheme is deployed to overcome some precepts of phenomenology that still inform much of the discourse on “the arts of the body.” Including the very idea of what a body is.

Check it out!