On May 16, the team behind Performance: Conservation, Materiality, Knowledge staged our third annual colloquium, a series of events investigating the conservation of performance from diverse perspectives. Seven artists who approach performance and its afterlives from different directions presented their work and ideas to an international audience watching online as well as a local audience at the Bern Academy of the Arts. In what follows, I will introduce each of the presenters and discuss their contribution to the event.

If you were unable to attend the colloquium, you can catch up with videos online. We’ll post a link here once they are available.

Christian Falsnaes

For Christian Falsnaes, art is an arena for staging social experiments. Born in Denmark in 1980, he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and is currently based in Berlin. He has had several solo exhibitions in Denmark and Germany, including 2018’s “Force” at the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum in Krefeld, and his work is featured in many public and private collections. Falsnaes’s performance works pose hard questions about the complex relationships between artist, performer, and viewer, while also implicating the political and institutional structures in which all three are enmeshed. Audiences may be invited, provoked, or dared to enter into the situations he stages. Past performances have led audiences to descend into debauched revelry (Feast, 2021); trash copies of problematic masterworks (Icon, 2018); or follow instructions that lead to uncomfortable or charged encounters with others (Justified Beliefs, 2014). “The audience is my material,” Falsnaes has said.

At the colloquium, Falsnaes explained that, with his instruction-based works, he has always tried to make audiences aware of the systems and power structures around them. As a result, he has recently made fewer pieces where he needs to be present to give the instructions (so that he as an individual is not the focus of the piece). This also makes it easier for museums to collect his pieces. He tries to give very clear written instructions about how the work should be carried out, though this doesn’t guarantee that misunderstandings won’t happen. He is very clear about what should and shouldn’t be documented for a given work. For example, First (2016), in the collection of the Centre Pompidou, involves filming one museum visitor every day, but the video is deleted at the end of the day; it’s not meant to be an archive, but rather a constantly-changing work. Yet its structure always remains the same. Thus the enduring and the fleeting are always in dialogue. Falsnaes also insists to museums collecting his works that even after the point of acquisition, he is able to make changes to a work while he is still around to do so. While some artists struggle to integrate their performance works with museum systems, Falsnaes takes these systems as his very subject. This both eases his works’ entry into art collections and complicates their relationship to such institutions.

Davide-Christelle Sanvee

Davide-Christelle Sanvee crafts rigorous, demanding performances that bring audiences’ attention to the spaces and bodies occupied by performer and viewer alike. Born in Togo in 1993, Sanvee has lived in Geneva since childhood. She graduated from the Geneva School of Art (HEAD—Haute école d’art et de design) and received a master’s degree from the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam, where her studies focused on architecture. In 2019 she won the Swiss Performance Prize. Sanvee uses performance to investigate architectural space, history, memory, personal identity, and relationships between people. Through archival research, architectural thinking, and physical movement, Sanvee embodies histories and ideologies latent in charged cultural spaces, such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris (Je suis pompidou.e.x, 2020), the Aargauer Kunsthaus (Le ich dans nicht, 2019), which houses Switzerland’s national art collection, or Geneva’s Pavillon ADC (À notre place, 2022). Her work has also archived, historicized, and discoursed upon the recent history of performance art in Switzerland (La performance des performances, 2022—which I wrote about about last year).

Sanvee—who had to be present over Zoom due to an injury—explained that she is interested in bringing to life things that are inanimate, whether buildings or people from the past. She also talked about the demands of taking on other people’s work, of trying to do the physically demanding things they have done with her different body and different set of skills. Sanvee spoke about “integration,” which has been a theme in her work in multiple ways. As a child immigrant to Switzerland and a Black woman from Togo, Sanvee has had to deal with what it means to “integrate” since she was very young. She said, “You have to in a way forget who you were in order to make a new you.” I find this very interesting in light of her works, notably La performance des performances, that reperform/reinterpret others’ performance pieces: in that piece, she very plainly does not forget who she was, but rather manages to integrate her own identity (and ideas, interests, body…) with the works of others. In this sense, Sanvee’s practice of what we might call archival performance offers a powerful model for reconsidering integration as innovation.

Pascale Grau

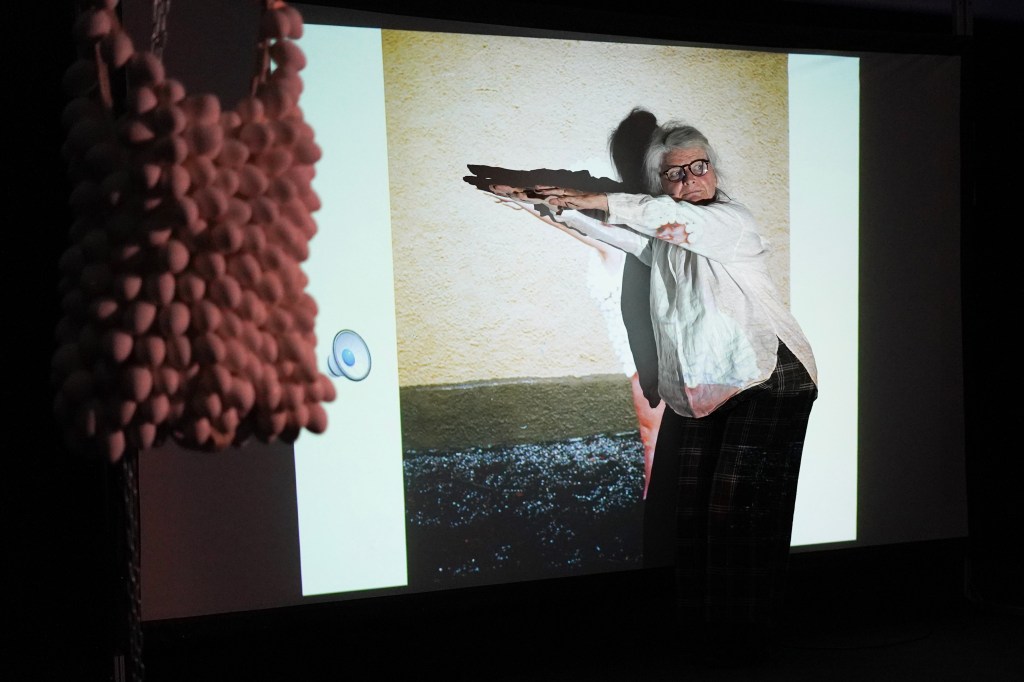

Pascale Grau understands performance as a practice of remembering, and sees the body as a storehouse of cultural memories. Born in Switzerland in 1960, she has made a powerful mark on the Swiss art scene and beyond through her performances, curation, scholarship, and teaching. She received a degree in modern dance at Heiner Carling’s HC Studio in Bern before studying art at the Hamburg University of Fine Arts and art theory at Zurich University of the Arts ZHdK. As a performer, Grau uses her own body to skewer the history of art, such as in 2019’s me as a fountain, which playfully subverts male artists’ claim to embody creativity: “From me spurts life, never-ending inspiration.” In Ovation (2005), which exists as both a live performance and a video, Grau performs a series of operatic bows towards the audience, only concluding the performance once they have begun to applaud her. In addition to various teaching and curatorial engagements, Grau has also championed the cause of performance documentation, working to ensure that performance art lives on through video, photography, interviews, and other means. From 2010–2012, she led the groundbreaking research project archiv performativ at Zurich University of the Arts.

At the colloquium, Pascale Grau presented a new version of Eisprung, originally performed in 1993, which she revisited in 2012 and 2016, and which has continued to exist in multiple forms: as a very fragile costume of eggshells sewn onto an old bathing suit; as a multifaceted performance with this costume at its heart, for which Grau jumped into water and let the eggshells break from the impact; as Super 8 films, lost, recovered, and reconstructed; and as digital documentation of subsequent performances, often involving video footage or still images projected over Grau’s live body. This was also the case here: Grau didn’t wear the (most recent version of the) costume, which is now too fragile due to the aging elastic (the bathing suit belonged to her mother), but she did commune with earlier versions of herself, projecting a photograph of an earlier Grau wearing the costume with arms outstretched, ready to jump into the water, and matching her live body to the image projected against the screen. In doing so, she asked the audience to consider the different layers of practice and documentation, and how they together create the story of the work. I thought this choice to unite various versions of herself was especially poignant given its subject matter of the “performance” of a woman’s body—the monthly ovulation or Eisprung (literally “egg jump”), which costs a woman energy, time, and pain regardless of whether she wishes to bear children or would rather use her physical energies to create art instead. Grau’s project also allows her the opportunity to explore the multifarious meaning and symbolism of the egg—something at once very fragile and marvelously strong, which we came to understand as a metaphor for performance itself seen through the lens of conservation. At the end of her performance/lecture, Grau asked us—an audience filled with conservators and other art professionals—to tell her how she might conserve the now-retired costume, which—perhaps surprisingly—is fragile not due to the surprisingly robust (and replaceable) egg shells, but to the bathing costume that was once worn by Grau’s mother, and which connects Eisprung to an earlier generation. (If you have ideas about how to conserve Grau’s costume, you are warmly invited to contact her directly.)

Ido Feder

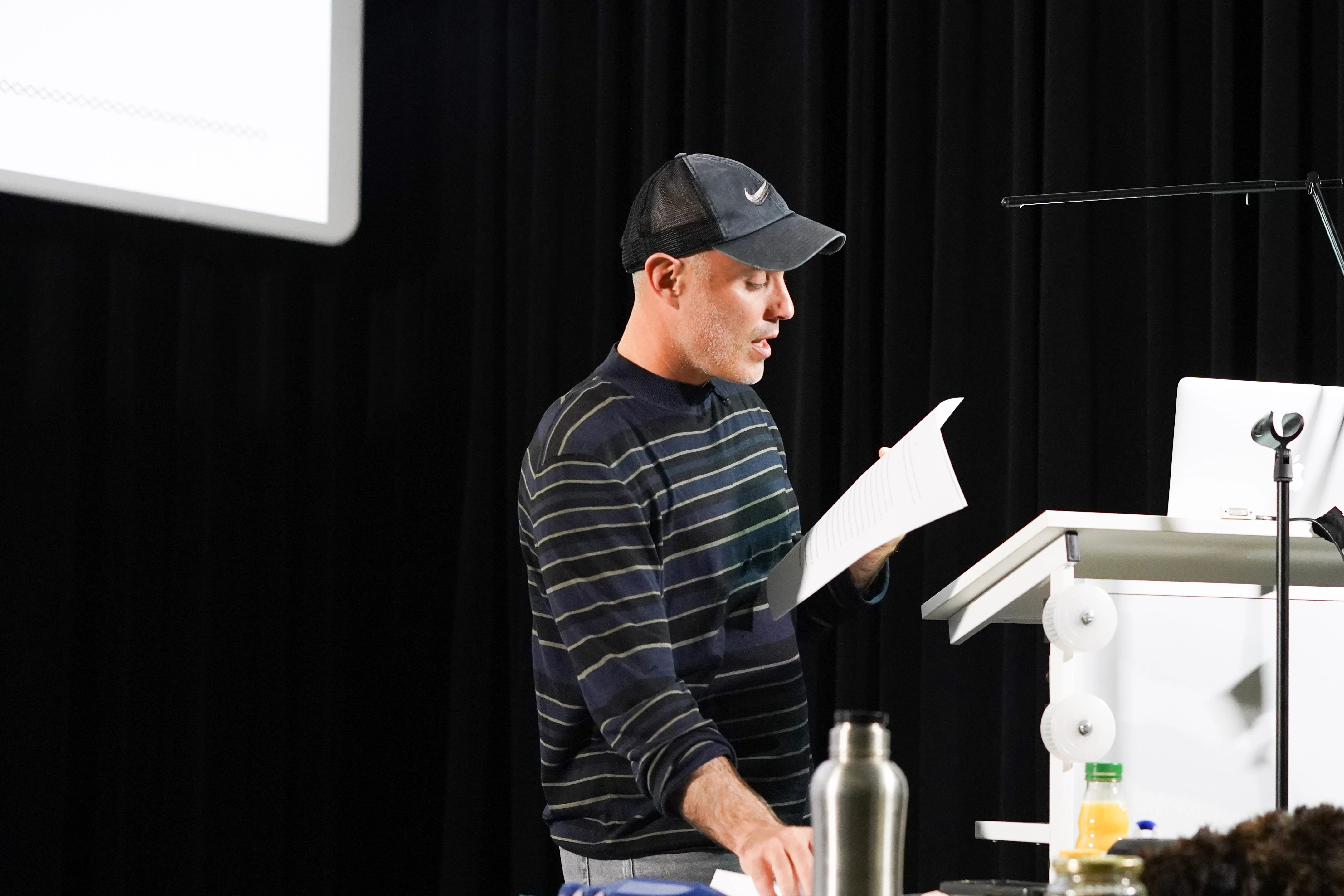

Ido Feder, born in 1985, is an Israeli choreographer, performance curator, and artistic director, whose work explores extended choreography, gang formation and dance and performance ceremonies. He is the artistic director of Tel Aviv-Jaffa’s Diver Festival, as well as a founder of the dance platform Tights: Dance and Thought and of the La Collectiz! group of progressive Israeli dancers. Feder has presented his works on all major stages in Israel, as well as internationally. Feder, who has also studied philosophy, investigates how dance’s heritage might be transformed in the present as well as in the future. In 2019’s At Hand! (Hebrew hicon, meaning “get ready” or “on your mark”), a group of dancers learned, reproduced, and reimagined iconic, sometimes demanding movements and gestures from performance works of the 1960s and ‘70s. For Feder, this return to performance’s past, in which dancers attempt to turn their bodies into “artistic objects,” also represents preparation for a world yet to come.

At the colloquium, Feder presented his own theories of performance and performativity, explaining how these express themselves politically. For him, performative logic can be a method for protecting and conserving humanity/the human (his ultimate goal), but at the same time, performative logic is a byproduct of capitalist logic, which must be somehow overcome. He introduced a number of clever neologisms to make this argument, of which the central concept was “privilogos,” which he sees as an antidote to the capitalist essence of performativity. Rather than keeping us mired in privilege, privilogos is a way of mobilizing the inherent resources of art to move past unproductive binaries. Feder then explained how he tries to make this happen in his own work as a choreographer, festival director, and educator. He sees performance conservation as the “mythos of privilogos”—the attempt to preserve the human through art.

To learn more about Feder’s work, watch his Two Questions interview with Hanna Hölling.

Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė

Dorota Gawęda and Eglė Kulbokaitė work collaboratively across a range of media, extending from painting and sculpture to performance and video, and even into fragrance, reaching the point “where language breaks down and one genre morphs into many.” Their artistic research weaves together ecology and technology, science and magic. Gawęda, born in Poland in 1986, and Kulbokaitė, born in Lithuania in 1987, both graduated from the Royal College of Art in London in 2012; today, they live and work in Basel. Gawęda and Kulbokaitė have had recent solo exhibitions at Palermo’s Istituto Svizzero, Palermo, Sofia’s Swimming Pool Projects, the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf, Fri Art – Centre d’Art de Fribourg, Futura in Prague, and London’s Cell Project Space, among several galleries and art centers. In 2022, they received the Allegro Prize as well as CERN’s Collide Residency Award. They are also the founders of YOUNG GIRL READING GROUP (2013– 2021). Gawęda and Kulbokaitė’s multifaceted approach to performance is exemplified by their creation and use of RYXPER1126AE, a fragrance that synthesizes odor compounds captured during their 2018 performance YGRG159 : SULK. The artists subsequently incorporated this fragrance into new, sculptural works, thus concretizing the ephemeral into a stable molecular structure while dissipating the performing body into an invisible, amorphous cloud.

Gawęda and Kulbokaitė explained how they want their work to be both futuristic and archaic at once. They are interested in using folklore and myths from Eastern Europe as source material, but these are transformed in narrative, image, and medium into something entirely new that also gestures at the hidden futures inherent in old stories. Multiple media—painting, sculpture, video, costume, live performance, fragrance—are so embedded in each of their works that it is difficult to separate them. Video, for example, is not merely a record of a performance, but a way of engaging with performance. They have done some work with creating and using fragrances in exhibitions, and talked about using fragrance as a form of olfactory documentation. Since their work takes so many forms, they are open to it being preserved in different forms (for example, if only a scent remains). It seemed that, for Gawęda and Kulbokaitė, thinking of how their work should be preserved for the future was a new and challenging perspective. Like so many artists at an early stage in their careers, they are more focused on other questions that relate more to today than tomorrow—making their work and getting it shown in the way that they want it to be seen.

Rosanna Raymond

Rosanna Raymond, born in Aotearoa (New Zealand) in 1967, has a multifaceted practice that encompasses performance, institutional critique, fashion, writing, curation, and pedagogy. Her work mediates Pacific Islander culture between museum and living tradition, academy and nightclub. Raymond received the Arts Pasifika’s 2018 Senior Pacific Artist Award, and is a member of the New Zealand Order of Merit. She has exhibited and presented her work in many institutions and communities around the world. Raymond’s performances—interventions into museum storerooms and crowded sidewalks—not only expose and critique the colonialism of traditional Western museum practices of conservation, collecting, and display, but also propose other methods for keeping culture alive, through inherited tradition, personal innovation, and embodiment. Her work, both independently and as a member of the collective Pacific Sisters, honors and extends the traditions she has inherited from her ancestors—Raymond has Sāmoan, Tuvaluan, Irish and French heritage—while insisting on Pacific Islander culture as modern, dynamic, hybrid, and individual. A formative early work is G’nang G’near (1993), which began life as a pair of Levi’s jeans and denim jacket that Raymond embellished with scraps of traditional, decorative tapa barkcloth that she found discarded when people cleaned out their homes. Raymond wore G’nang G’near in art, fashion, music, and social settings before the outfit was accessioned into a museum collection. For Raymond, all heritage, whether tangible or intangible, is alive, and thus requires living performance and reembodiment for its continued flourishing. Her 2021 master’s thesis, “C o n s e r . V Ā . t i o n | A c t i . V Ā . t i o n: Museums, the body and Indigenous Moana art practice,” addresses both practical and theoretical models for conserving Pacific Islander heritage in museums through performance.

When Raymond took the floor at the colloquium, she asked us all to chant with her: “I am the house of the ancestor. I live through them and they live through me.” She encouraged us to invite our ancestors in to share the space with us, emphasizing that sharing space with ancestors transcends gender and other forms of personal or bodily specificity. She discussed how she developed her own understanding of “sharing space” with ancestors: This means that she does not become another person, goddess, or semi-made up character (her performance practice involves costumes meant to evoke hybrid, ancient/modern, idiosyncratic ancestor figures), but rather that she makes space for them to coinhabit her body with her. Raymond has made the Moana concept of Va central to her notions of art and its relationships to past, present, future, tradition, museum, and beyond: conserVAtion, actiVAtion, even saVAge. Va is difficult to define—she said that before the work of a few recent, pioneering scholars such as Albert Wendt (who is also a novelist and poet), there was a lack of functional written definitions of it—but she described it as “An active space, that binds people and things together, forming relationships that necessitate reciprocal obligations.” The Va Body, a central concept in her performance practice, allows her to understand performance as bringing relationships between people and things, past and present, together within her own body. Raymond also discussed the difficulty (though not impossibility) of selling her work (often costumes from characters that have been “retired”) to institutions. Her work is both contemporary art and Moana tradition, which means it needs to be conserved with sensitivity to both of these identities. One examples of this is allowing costumes to be occasionally worn, rather than insisting that they stay in a box or on a mannequin. She considers this good for the “objects” as well as for the living (sub)cultures they belong to.

Conclusions

Each presentation introduced a very different body of work and approached performance and its afterlives from a unique angle. Yet connections, resonances, and entanglements between the different speakers’ projects and ideas arose continuously throughout the day. A perpetual theme was that of conservation as transformation. That might mean transformation into a new medium, as in the work of Falsnaes, Gawęda and Kulbokaitė, or Grau, which slides between different formats even within the same work. This might also mean transformation into a new body and a new subjectivity, as in Sanvee’s archival performances, or the transformation of an ancient collective tradition into something that is contemporary, changing, and personal, as in Raymond’s costumes. Feder also transformed privilege intro privilogos, finding new possibilities for performance’s theoretization and continuation. I was also struck by the various transformation of age—aging materials, aging bodies—and I noticed that our younger speakers tended to have different questions and different answers from those who were older and more experienced. Another theme common to all of the artists was the question of costume—especially taken in a wider sense to include wearing clothing, adorning one’s own skin, or playing a role. Such engagement with the costume—the question of what we put on or remove from the body—encompassed everything from simple outfits of jeans and a t-shirt and traditional garments to a plush, smiling version of a staircase, tattoos, and even eggs. In retrospect, I find myself reflecting on a concept that Raymond introduced, that of “recharging” a performance, object, character, etc., imbuing it with new life and purpose while respecting its origins. Moving forward, “recharging” might serve as an alternative to—or at least a complication upon—the fraught term “reperformance.”

Featured image: Concluding discussion. Photo by Aga Wielocha.